Biography of Benjamin Franklin

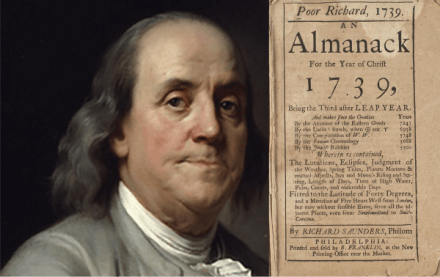

In addition to being a founding father, Benjamin Franklin was a polymath, scientist, printer, politician, freemason, and diplomat. He worked as an editor, bookseller, statesman, researcher, innovator, writer, political theorist, and printer. Franklin was one of the founding fathers of the United States, a renowned thinker, a co-author and authenticator of the American Declaration of Independence, and the nation's first postmaster general. Franklin was christened at the Old South Meeting House on January 17, 1706, the day following his birth on Milk Street in Boston, Massachusetts. Benjamin Franklin's father, Josiah Franklin, was a tallow trader, soap manufacturer, and candle manufacturer. On December 23, 1657, Josiah Franklin was born in Ecton, Northamptonshire, England. He was the son of a peasant and a blacksmith, Thomas Franklin and Jane White, respectively. Benjamin's grandparents and his father were born in England. With his two marriages, Josiah Franklin had a total of seventeen kids. After getting married to Anne Child in Ecton in 1677, the couple moved to Boston in 1683. They had three kids before leaving Ecton and four afterward. He married Abiah Folger on July 9, 1689, in the Old South Meeting House after his first wife, Anne, passed away, and they had ten kids together. Their eighth child, Benjamin, was Josiah Franklin's fifteenth total child and his tenth and last son with his second wife. Abiah Franklin, the mother of Benjamin Franklin, was born on August 15, 1667, in Nantucket, Massachusetts Bay Colony, to Peter Folger, a miller, and educator, and Mary Morrell Folger, a domestic servant. When King Charles I of England started torturing Puritans in 1635, Mary Folger's Puritan family was one of the first to migrate to Massachusetts in search of religious freedom. They departed for Boston the same year. Peter Folger was "the sort of rebel destined to transform colonial America". He was imprisoned from his position as a court clerk for disrespecting the local magistrate and standing up for working-class store owners and craftsmen who were in dispute with rich landowners. Escape to PhiladelphiaTrying to escape was prohibited. In early America, everyone had to be accepted by society, and escaping had no place in society. Ben, who wished to work as a printer, boarded a boat for New York. Instead, he crossed New Jersey on foot before taking a boat to Philadelphia. He spent the rest of his money on some rolls after his departure. On October 6, 1723, when his future wife, Deborah Read, first met him, he was wet, filthy, and untidy. She felt he had a strange appearance and had no idea that seven years later, they would be married. Franklin gained employment as a trainee printer. As a result of his success, the governor of Pennsylvania pledged to help young Franklin start his own company if he merely traveled to London to purchase typefaces and printing materials. Franklin traveled to London, but because the governor violated his pledge, Benjamin was compelled to work as a printer for a few months in England. Before he went to London, Benjamin resided with the Read family. Deborah Read, the same girl who had watched young Benjamin come to Philadelphia, began conversing with the young printer about getting married. But Ben wondered whether he was prepared. She married another man while he was away. Franklin attempted to run a business when he got back to Philadelphia, but he quickly returned to working as a printer's assistant. Franklin established himself in the printing industry because he was a better printer than the man he was employed. Philadelphians began to observe and notice Franklin since he appeared to be always working. He soon started receiving government contracts and proposals. Benjamin had a son named William in 1728. William's mother's identity remains unknown. Eventually, Benjamin wed Deborah Read, his childhood love, in 1730. Deborah was now able to marry because her spouse had left her. The Franklins had their own business during this period, selling everything from soap to fabric, in addition to owning a print shop. Ben had a bookstore too. The Pennsylvania GazetteBenjamin Franklin acquired the Pennsylvania Gazette, a newspaper, in 1729. Franklin not only printed the newspaper but frequently supplied items to it via aliases. His publications quickly rose to the top of the colonies in terms of readership. This publication was among the first to publish the first political cartoon drawn by Ben. The Franklin dedication to public benefit began to emerge in the 1720s and 1730s. He founded the Junto, an organisation of young working men devoted to civic and self-improvement. He had become a Mason and had become a popular and busy person socially. Apprentice PrinterThe New England Courant, Boston's first "newspaper," was founded by his brother when Benjamin was 15 years old. Before James's Courant, the city had two newspapers, but they solely republished news from other countries. James' newspaper published news about ship timetables, editorials written by James' friends, adverts, and articles. Although Benjamin also desired to contribute to the publication, he was aware that James would never permit him. Benjamin was an apprentice, after all. Ben started using the name of an imaginary widow named Silence Dogood to sign his letters and started publishing them late at night. Dogood was a wealth of knowledge and a harsh critic of the world, especially when it came to the problem of how women were treated. So that no one would know who was authoring the pieces, Ben would smuggle the letters under the print shop door at night. Everyone wanted to know who the actual "Silence Dogood" was because her publications were big hits. After fourteen letters, Ben acknowledged that he had been writing the letters. James scolded his brother and was quite unhappy with the attention given to him, while Ben's mates found him to be rather intelligent and hilarious. The Franklins quickly became at odds with Boston's influential Puritan preachers, the Mathers. In those days, smallpox was a fatal illness, and the Mathers favoured immunisation; the Franklins thought it merely made people weaker. While the majority of Bostonians supported the Franklins in the discussion, many did not appreciate the way James made fun of the clergy. In the end, James was imprisoned for his opinions, and Benjamin was left in charge of the newspaper for a while. James was not pleased with Ben for continuing to publish the publication after his release from prison. Instead, he continued to mistreat and assault his younger brother. In 1723, Ben chose to go because he could no longer stand it. Poor Richard's AlmanackFranklin, though, enjoyed his work. He began releasing Poor Richard's Almanack in 1733. Weather information, recipe books, predictions, and homilies were all included in the regular almanack of the time. In the context of Richard Saunders, a vagabond who needed money to support his unhappy wife, Franklin released his almanack. Franklin's humorous aphorisms and engaging writing set his almanack apart. Poor Richard is the source of some well-known Franklin quotes, including "A penny saved is a penny earned." Fire PreventionFranklin kept giving information and updates to his community throughout the 1730s and 1740s. He assisted in starting initiatives to farm, clean, and illuminate Philadelphia's streets. He began campaigning for environmental restoration. Franklin was extremely successful during this time period for his participation in the 1731 founding of the Library Company. Books in this era were costly and available in limited quantity. Franklin understood that people could obtain books from England by sharing their money. The country's first subscription library was therefore established. He contributed to founding the American Philosophical Society, the country's first educational society, in 1743. Franklin gathered a group who established the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751 after discovering the area needed additional services for treating the ill. Today, the Library Company, the Philosophical Society, and Pennsylvania Hospital still exist. Franklin started working to devise a solution since fires created a serious hazard to Philadelphians. He established Philadelphia's first fire company, the Union Fire Company, in 1736. His aphorism, "An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," was originally supposed to be used in firefighting. Those who sustained fire damage to their living spaces generally faced lasting economic damage. Franklin thus led to the formation of the Philadelphia Contribution for Insurance Against Loss by Fire in 1752. Those who had insurance did not suffer economic disaster. Today, The Contribution is still running. InventionsElectricityIn the 1730s and 1740s, Franklin's printing company was flourishing. Moreover, he began forming franchise printing alliances in other regions. He gave up his company in 1749 and began focusing on science, research, and innovations. Franklin was accustomed to this. He created the Franklin stove, a heat-efficient stove, in 1743 to assist in effectively raising temperatures in homes. He declined to obtain a title because he believed that the furnace was created to benefit the public. Swimming fins, the glass armonica (a musical instrument), and bifocals are among Franklin's achievements. He began his research on electricity at the start of the 1750s. Franklin gained worldwide recognition for his research, notably for his kite experiment that demonstrated the nature of electricity and lightning. OceanographyFranklin became interested in the North Atlantic Ocean circulation patterns while serving as deputy postmaster. In 1768, he was in England when he emerged from a Colonial Board of Customs grievance: Why did British cargo ships carrying letters take many more days to arrive in New York than a typical commercial ship took to arrive in Newport, Rhode Island? The parcels left from Falmouth in Cornwall, but the merchant ships went from London, making their journey lengthier and more complicated. Franklin asked his Nantucket whaler captain cousin, Timothy Folger, about it, and Timothy remarked that commerce ships regularly abandoned the idea of a powerful easterly mid-ocean current. The commanders of the postal packets drove directly into it, facing a 3 mile per hour (5 km/h) opposing current. Franklin studied with Folger and other expert naval officers, obtaining the knowledge necessary to map the current and give it the term that is still recognized today, the Gulf Stream. Experiments and TheoriesFranklin was the only prominent scientist to accept Christiaan Huygens's wave theory of light, which was largely rejected by the rest of the scientific world. He did so together with his contemporaries, Leonhard Euler and John Stuart Mill. Isaac Newton's corpuscular hypothesis was universally accepted in the 18th century, and it required Thomas Young's famous slit experiment in 1803 to convince the majority of scientists to accept Huygens's concept. An urban legend holds that on October 21, 1743, a storm coming from the southwest hindered Franklin from seeing a lunar eclipse. He was reported to have noticed that, in contrast to his expectations, the predominant winds were coming from the northeast. Although Boston lies northeast of Philadelphia, he discovered that exactly the same storm did not arrive there until following the eclipse. His conclusion that storms don't necessarily move in the direction of the wind blowing had a big impact on meteorology. Franklin made observations on the link between the Laki volcanic eruption in Iceland in 1783 and the ensuing severe European winter of 1784. He gave a series of lectures regarding this topic. On a scorching day, Franklin noticed that he stayed cooler in a wet shirt in the wind than he was in a dry shirt, which led him to note the existence of a principle of refrigeration. He carried out experiments to get a better understanding of this phenomenon. He and colleague John Hadley performed an experiment in 1758 at Cambridge, England, where they repeatedly hydrated a mercury thermometer's ball with ether and used bellows to vaporize the ether. The thermometer recorded a decreasing temperature with each succeeding evaporation, dropping to 7 �F (about -14 �C) at the end. The room's temperature remained consistent at 65 �F (18 �C), according to another thermometer. In his article Cooling by Evaporation, Franklin stated that "one may consider the probability of freezing a man to death on a hot summer's day." Political EnvironmentFranklin's involvement in politics increased during the 1750s. He travelled to England in 1757 to symbolize Pennsylvania in a conflict with the Penn family's heirs about who should portray the Colony. He stayed in England until 1775, serving as a colonial delegate for Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, as well as Pennsylvania. Franklin thought of himself as an obedient Englishman when he first went to live abroad. Many of the conveniences that America lacked were present in England. Furthermore, the country had the humorous conversation, theatre, and brilliant thinkers?all of which were scarce in America. Deborah was continually invited to travel to England to see him. She was scared of travelling by ship, but he had thought of remaining there forever. Franklin was taken aback by America's strong resistance to the Stamp Act in 1765. His statement in front of the legislature influenced the lawmakers to abolish the rule. He started considering if America ought to separate from England. Despite having many friends in England, Franklin had become tired of the corruption he observed in both political and royal circles. Franklin, who had suggested a strategy for unified colonies in 1754, can now diligently continue achieving that objective. Franklin's "Hutchinson Affair" was his big break with England. Massachusetts's governor was selected for the English as Thomas Hutchinson. He had been working for the King, even if he was supposed to support the people of Massachusetts in their claims against England. Franklin obtained some of Hutchinson's letters in which he demanded "an abridgement of what are called English Liberties" in America. He delivered the letters to America, where many people were shocked. Franklin was summoned to Whitehall, the English Foreign Ministry, where he had been openly criticized for leaking the letters.

Junto and LibraryFranklin founded the Junto, an organization of "similar-minded aspiring artists and businessmen who sought to develop themselves alongside helping their area," in 1727 when he was 21 years old. The Junto was a meeting place for people to discuss social issues, and it was the birthplace of many Philadelphia organizations. The Junto was designed after English coffeehouses that Franklin was familiar with and served as hubs for spreading social reform in Britain. The Junto loved to read, but books were extremely limited and expensive. The participants established a library originally composed of their own works after Franklin stated: I put forward the idea that since we usually referred to our books in our discussions of the investigations, it might be practical for us to have them all together where we met so that they could occasionally be engaged. By grouping our books into familiar libraries, we would still be capable of keeping them together while giving us all the benefit of utilizing the books of all of our other members, and it would be almost as advantageous as if we all owned the entire collection. But this was insufficient. Franklin came up with the concept of a subscription library, where users would share their money to purchase books for everyone to read. The Library Company of Philadelphia was established in this way; he wrote its charter in 1731. He acquired Louis Timothee, the country's first librarian, in 1732. The Library Company is now a leading educational and technical library. Agent for British and Hellfire Club MembershipDuring his time in England in 1758, Franklin is reported to have periodically participated in the Hellfire Club meetings as a non-member. But some writers and historians claim that he was a British spy. Since no documentation exists (they were destroyed in a fire in 1774), a number of these members are known to each other because of the letters through which they communicated. Donald McCormick, a historian with a reputation for making disputed statements, was one of the first to argue that Franklin was a double agent and a member of the Hellfire Club. A New NationHe began to make a concerted effort for independence. Unsurprisingly, he believed that his son William, currently the Imperial governor of New Jersey, would accept his ideas. But William omitted his ideas. William continued to be an English loyalist. As a result, there was a split between the father and son that was never fully re-conciled. Franklin served on a five-person committee that assisted in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence after being nominated to the Second Continental Congress. Although Thomas Jefferson did much of the writing, Benjamin Franklin made the majority of the contributions. Franklin approved the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and then proceeded to France to function as an envoy to Louis XVI's court. Franklin was admired in France. The modest American, who looked like a backwoodsman and yet could fit any intelligence in the world, was the person who had mastered lightning. He stumbled over his French words as he spoke. He was quite well-liked by the ladies. Benjamin had been a notorious flirt after the death of his wife, Deborah. The French government approved a Treaty of Alliance with the Americans in 1778, partially due to Franklin's reputation. Franklin further assisted in obtaining funds and convincing the French that they were acting morally. Following the American victory in the Revolution, Franklin was there to sign the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Franklin, who was now in his late 70s, came back to the United States. He was elected Executive Council President of Pennsylvania. He participated in the Constitutional Convention as a delegate and affixed his signature to the Constitution. In 1789, he published a treatise opposing slavery, which was one of his final acts in public. On April 17, 1790, Franklin passed away at the age of 84. The cremation of the gentleman, termed "the harmonic human multitude," was accompanied by 20,000 people. Achievement As a WriterMuch of Franklin's well-known status is based on his publication of the famous Poor Richard's Almanack in 1733 under the alias Richard Saunders, which included both original and borrowed content. He commonly used aliases while writing. He had established a unique, identifiable writing style that was straightforward, sensible, and featured declarative sentences with a clever, gentle, yet self-deprecating attitude. His Richard Saunders figure always refused to be the author, despite the reality that was widely acknowledged. Old sayings from this almanack known as "Poor Richard's Proverbs," such as "A penny saved is two pence dear" (commonly misreported as "A penny saved is a penny earned") and "Fish and guests stink in three days," are still widely used today. In traditional society, being knowledgeable meant having an appropriate adage for each situation, so his audience has always been willing. Ten thousand units were sold annually, and it became a masterpiece. For all of the British Plantations in America, Franklin decided to publish The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle in 1741. The Prince of Wales' royal emblem was used as the book cover. Father Abraham's Sermon, commonly referred to as The Way to Wealth, was published by Franklin in 1758, the same year he stopped contributing to the Almanack. Franklin's autobiography, which he started to write in 1771 but couldn't be published until after his death, has become a model in the field. In a letter titled "Advice to a Friend on Choosing a Mistress," dated June 25, 1745, he counsels a young man on how to control his sexual desires. It was not included in volumes of his papers during the nineteenth century because of its licentious character. Federal court rulings from the middle to the end of the 20th century used the content to argue against censorship and invalidate obscenity laws.

Declaration of IndependenceAfter his second visit to Great Britain, Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775. By that time, the American Revolution had started, with clashes between colonists and the British arising at Lexington and Concord. The major British army was compelled to stay in Boston by the New England military. Franklin was enthusiastically elected by the Pennsylvania Assembly to represent them at the Second Continental Congress. He was positioned to be a member of the Committee of Five that composed the Declaration of Independence in June 1776. Although he was momentarily unable to participate in most committee meetings due to gout, he made a number of "minor but significant" revisions to the text that Thomas Jefferson had delivered to him. He is recorded as saying, "Yes, we must; indeed, all hang together, or most certainly we shall all hang individually," in response to John Hancock's remark that they should all enjoy together at the signings. Legacy of Benjamin FranklinFranklin provided significant political help to the founding of the United States even after he believed that public service was more powerful than science, despite his enormous scientific accomplishments. He participated in the formation of the Declaration of Independence, helped to write the Articles of Confederation, which served as America's first national Constitution, and was the oldest delegate to the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention in 1787, which drafted the United States of America's Constitution. More interestingly, he was a key player in the commission that tried to negotiate the treaty through which Great Britain acknowledged its former 13 colonies as sovereign nations and served as the new American republic's strategic representative in France during the Revolution, safeguarding both international legitimacy and financial and military aid from the government of Louis XVI. He can quite reasonably be recognized as America's finest diplomat since nobody else could have done all that he did in France during the Revolution. Perhaps equally important were Franklin's numerous contributions to daily security and comfort, particularly in Philadelphia, his beloved hometown. To his attention, no public initiative was too big or minor. He also created the armonica, bifocal spectacles, the odometer, and the Franklin stove, a wood-burning burner that heated American households for more than 200 years. He had notions about everything, including the characteristics of the Gulf Stream and what causes the common cold. He brought up the ideas of Daylight Saving Time and matching grants. He contributed to the establishment of democratic governance for Philadelphians almost exclusively on his own. In addition, he contributed to the founding of several modern institutions, including a hospital, a school, an insurance business, a fire agency, and a library.

Next TopicBetty White

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share