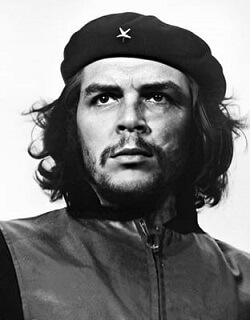

Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14 June 1928 - 9 October 1967) was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, writer, guerrilla commander, diplomat, and military strategist. His stylised visage, as a pivotal character in the Cuban Revolution, has become a ubiquitous countercultural emblem of defiance and a worldwide insignia in popular culture. Guevara travelled around South America as a young medical student, becoming politicised by the poverty, malnutrition, and sickness he observed. His growing determination to help end what he saw as the United States' economic exploitation of Latin America led him to participate in Guatemala's social reforms under President Jacobo Arbenz, whose subsequent CIA-assisted ouster at the request of the United Fruit Company solidified Guevara's political beliefs. Guevara held key posts in the new Cuban administration following the revolution. Such positions also enabled him to play a crucial part in training militia fighters to fight back against the Bay of Pigs invasion, as well as delivering Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles to Cuba ahead of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Guevara was also a prolific writer and diarist, publishing a basic guerrilla warfare manual and a best-selling book on his youth continental experiences on motorcycle travels. His experiences and study of Marxism-Leninism led him to conclude that underdevelopment and dependency in the Third World Company were inevitable byproducts of imperialism, neocolonialism, and monopoly capitalism and that the only answers were proletarian internationalism and world revolution. Guevara escaped Cuba in 1965 to encourage African and South American revolutions, first in Congo-Kinshasa. Subsequently, in Bolivia and amidst all this, he was caught and killed by CIA-assisted Bolivian forces. Guevara is a renowned and loathed historical figure, split in the communal imagination through a plethora of biographies, memoirs, essays, documentaries, songs, and films. Guevara has been a defining figure for many left-wing organisations as a result of his imagined martyrdom, literary invocations for class struggle, and goal to establish the awareness of a "new man" motivated by moral rather than material objectives. On the other side, his political opponents on the right accuse him of embracing authoritarianism and promoting violence against his opponents. His Early LifeErnesto Guevara was born on June 14, 1928, in Rosario, Argentina, to Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna y Llosa. Although he was born Ernesto Guevara, he was also known as "de la Serna" and/or "Lynch." He was the eldest of five children in an upper-class Argentine family with Basque, Spanish (Cantabrian), and Irish ancestors. Luis Mara Peralta, a rich Spanish landowner in colonial California, and Patrick Lynch, who came from Ireland to the Ro de la Plata Governorate, were two of Guevara's renowned 18th century relatives. "The first thing to notice is that the blood of the Irish rebels went through my son's veins," Che's father observed in response to his son's "restless" demeanour. Ernestito (as he was then named) developed an early "passion for the destitute." Guevara was exposed to a wide range of political viewpoints as a child, growing up in a household with Marxist leanings. His father, an ardent supporter of Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, would welcome soldiers of the battle at his house. He thrived as an athlete despite terrible spells of acute asthma that plagued him for the rest of his life, enjoying swimming, football, golf, and shooting, as well as becoming an "untiring" motorcycle. His Literary InterestGuevara learnt chess from his father and began competing in local competitions when he was 12. He planned to devote his entire life to studying poetry, namely that of Pablo Neruda, John Keats, Antonio Machado, Federico Garca Lorca, Gabriela Mistral, César Vallejo, and Walt Whitman. He also remembered If- by Rudyard Kipling and Martn Fierro by José Hernández by heart. Guevara's home included over 3,000 volumes, allowing him to be a voracious and varied reader with interests from Karl Marx to William Faulkner, André Gide, Emilio Salgari, and Jules Verne. Among his favourite authors were Anatole France, Friedrich Engels, H. G. Wells, Robert Frost, and Jawaharlal Nehru, as well as Franz Kafka, Albert Camus, Vladimir Lenin, and Jean-Paul Sartre. He became interested in Latin American writers such as Horacio Quiroga, Ciro Alegra, Jorge Icaza, Ruben Daro, and Miguel Asturias as he grew older. Many of these writers' ideas he catalogued in his own handwritten notes on key thinkers' concepts, terminologies, and philosophies. Analytic sketches of Buddha and Aristotle were included, as well as analyses of love and patriotism by Bertrand Russell, society by Jack London, and other works. He was captivated by the theories of Sigmund Freud, with whom he discussed everything from dreams and libido to narcissism and the Oedipus complex. His favourite subjects to study included philosophy, mathematics, engineering, political science, sociology, history, and archaeology. A CIA "biographical and personality study" dated 13 February 1958 and declassified decades later praised Guevara's academic pursuits and intellect, characterising him as "very well read" and "quite bright for a Latino." Journey on MotorcycleIn 1948 Guevara started his studies about medicine in University of Buenos Aries. His hunger to travel the globe drove him to intersperse his scholastic ambitions with two long contemplative excursions that significantly transformed his perspective on himself and Latin America's current economic problems. The first trip, in 1950, was a solo journey of 4,500 kilometres (2,800 miles) across isolated northern Argentina provinces on a bicycle fitted with a modest motor. Guevara then spent six months at sea as an Argentine nurse on commercial marine freighters and oil tankers. He set off on a nine-month, 8,000-kilometer (5,000-mile) motorbike journey through South America in 1951. He skipped a year of school to travel with a buddy, Alberto Granado, with the ultimate goal of working at the San Pablo leper colony on Peru's Amazon River. Guevara was stunned by an overnight visit with a persecuted communist couple who didn't even have a blanket, characterising them as "the shivering flesh-and-blood victims of capitalist exploitation." He was astounded by the crushing poverty of the remote rural districts, where peasant farmers toiled small pieces of land owned by wealthy landowners, on his route to Machu Picchu. Later in his voyage, Guevara was particularly inspired by the brotherhood among the residents of a leper colony, remarking, "The finest kinds of human solidarity and loyalty develop among such lonely and desperate individuals." Guevara used notes from this trip to write The Motorcycle Diaries, which became a New York Times best-seller and was adapted into a film in 2004." Before returning to Buenos Aires, Guevara travelled for 20 days across Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and Miami, Florida. By the tour's conclusion, he had seen Latin America as a unified organism needing a continent-wide liberation plan rather than a collection of independent states. His vision of a borderless, unified Hispanic America with a shared Latino ancestry was a recurring motif in his later revolutionary operations. He finished his studies and obtained his medical degree in June 1953 after returning to Argentina. Guatemala and United Fruit

Guevara went off again on July 7, 1953, this time to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador. Before leaving for Guatemala on December 10, 1953, Guevara sent an update to his aunt Beatriz in San José, Costa Rica. Guevara describes his excursions across the United Fruit Company's jurisdiction in the letter, which convinced him that the company's capitalist structure was damaging to ordinary people. To intimidate his more conservative relatives, he adopted an aggressive tone, and the letter concludes with Guevara vowing on a picture of the recently died Joseph Stalin that he will not rest until these "octopuses" had been conquered. Later the same month, Guevara landed in Guatemala, where President Jacobo Arbenz led a democratically elected administration working to end the latifundia agricultural system through land reform and other programmes. President Arbenz had implemented a vast land reform programme to accomplish this, in which all uncultivated areas of extensive land holdings were to be confiscated and given to landless peasants. The United Fruit Company was the largest landowner and most affected by the changes; the Arbenz administration had already acquired over 225,000 acres (91,000 hectares) of uncultivated land from them. Guevara chose to establish his home in Guatemala to "improve himself and do whatever may be necessary in order to become a real revolutionary," since he was pleased with the direction the country was taking. Guevara sought out Hilda Gadea Acosta in Guatemala City, a Peruvian economist with political clout as a member of the left-wing Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA). She introduced Guevara to several high-ranking people in the Arbenz regime. During the July 26, 1953, raid on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba, Guevara contacted a group of Cuban exiles linked with Fidel Castro . He became well-known during this period for his frequent usage of the Argentine filler word Che (a multi-purpose discourse marker, like the syllable "eh" in Canadian English). Other Central American immigrants in Guatemala helped Guevara, and one of them, Helena Leiva de Holst, gave him with food and shelter while outlining her trips to study Marxism in Russia and China, for whom Guevara penned the poem "Invitación al camino." In May 1954, communist Czechoslovakia despatched a ship supplying infantry and light artillery armaments to the Arbenz administration, which arrived in Puerto Barrios. As a result, the United States government, which had been tasked by President Eisenhower with deposing Arbenz in the multifaceted CIA operation code-named PBSuccess since 1953, responded by bombarding Guatemala with anti-Arbenz propaganda via radio and air-dropped leaflets, as well as launching bombing raids using unmarked planes. The US also backed an armed group of several hundred anti-Arbenz Guatemalan exiles and mercenaries led by Carlos Castillo Armas to assist in overthrowing the Arbenz administration. On June 27, Arbenz announced his resignation. Armas and his CIA-backed men marched into Guatemala City, establishing a military junta that elected Armas as president on July 7. The Armas administration then solidified control by rounding up and killing suspected communists, smashing formerly thriving labour organisations, and undoing past agrarian improvements. Guevara was willing to fight for Arbenz and joined an armed militia formed by socialist youth for that reason. Guevara quickly returned to medical responsibilities, dissatisfied by that group's inactivity. Following the coup, he volunteered to fight again, but Arbenz quickly sought sanctuary in the Mexican consulate and instructed his international supporters to leave the country. Guevara's repeated demands to resist were observed by coup sympathisers, and he was slated for death. After Gadea was detained, Guevara took refuge inside the Argentine consulate, where he remained for many weeks until receiving a safe-conduct clearance and travelling to Mexico. Mexico and The PreparationOn September 21, 1954, Guevara came to Mexico City and began working in the allergy unit of the General Hospital and the Hospital Infantil de Mexico. His first wife, Hilda, writes in her biography My Life with Che that Guevara pondered becoming a doctor in Africa for a while and was distressed by the poverty surrounding him. Hilda mentions Guevara's fascination with an elderly washerwoman he was treating, observing that he considered her a "symbol of the most neglected and mistreated class." Hilda later discovered a poem written by Che for the old woman that featured "a vow to struggle for a better society, for a better life for all the impoverished and mistreated." During this period, he reconnected with López and the other Cuban exiles he met in Guatemala. López introduced him to Fidel Castro, the revolutionary leader who created the 26th of July Movement and was now plotting to destabilise the administration of Fulgencio Batista. During a lengthy chat with Fidel on the night of their first encounter, Guevara determined that the Cuban cause was the one he had been looking for, and by morning he had joined the 26th of July Movement. By this stage in his life, Guevara believed that US-controlled businesses had imposed and backed authoritarian regimes all over the world. In this sense, he saw Batista as a "US puppet whose strings needed to be broken." Despite his intention to be the group's battlefield medic, Guevara engaged in military training alongside the Movement's members. The most important aspect of the training was understanding guerrilla warfare's hit-and-run tactics. Guevara and the others endured 15-hour marches across mountains, rivers, and deep foliage, learning and refining ambush and swift retreat techniques. Guevara was teacher Alberto Bayo's "prize pupil" among those in training from the outset, achieving the highest on all exams given. General Bayo dubbed him "the best guerilla of them all" at the completion of the training. In September 1955, Guevara married Gadea in Mexico before departing with his intention to aid in the liberation of Cuba. Cuban RevolutionThe Granma, an old, leaky cabin cruiser, was the initial stage in Castro's revolutionary plot to attack Cuba from Mexico. On November 25, 1956, they set sail for Cuba. Many of the 82 soldiers were killed in the combat or executed upon capture after being attacked by Batista's forces immediately after landing; only 22 survived. During the initial bloodbath, Guevara abandoned his medical supplies and picked up a crate of ammo dropped by a fleeing comrade, which proved to be a watershed event in Che's life. Only a few revolutionaries survived, emerging as a battered combat force deep in the Sierra Maestra mountains, aided by Frank Pa's urban guerrilla network, the 26 July Movement, and local Campesinos. With the party gone to the Sierra, the world was left wondering if Castro was alive or dead until a New York Times interview with Herbert Matthews was published in early 1957. The piece portrayed Castro and the guerrillas in a lasting, almost legendary light. Guevara was not there for the interview, but he realised the value of the media in their campaign in the following months. During Guevara's time concealed among the destitute subsistence farmers in the Sierra Maestra highlands, he learned that there were no schools, no electricity, minimal access to healthcare and that more than 40% of people were illiterate. As the battle progressed, Guevara joined the rebel forces and convinced Castro with skill, diplomacy, and patience. Guevara established grenade factories, bread bakeries, and schools to teach illiterate Campesinos to read and write. Guevara also developed health clinics, military tactics courses, and a newspaper to distribute knowledge. Guevara, as second-in-command, was a stern disciplinarian who occasionally shot defectors. Deserters were treated as traitors, and Guevara was known to dispatch teams to follow down individuals attempting to flee their duty. As a result of his brutality and ferocity, Guevara was feared. According to one biographer, his technical notations and matter-of-fact description demonstrated an "exceptional detachment to violence" at that juncture in the fight. Guevara reached Havana the next day, on January 2, to gain complete control of the capital. Fidel Castro arrived six days later after stopping to collect support in numerous major towns on his approach to triumphantly entering Havana on January 8, 1959. Two thousand individuals were killed in the two years of revolutionary combat. Guevara travelled to a vacation house in Tarará to recover from a severe asthma attack in mid-January 1959. During his time there, he founded the Tarara Group, which debated and developed new strategies for Cuba's social, political, and economic growth. In addition, while recovering at Tarara, Che began writing his book Guerrilla Warfare. Guevara was declared "a revolutionary" by the revolutionary government in February. Guevara headed a new column of rebels pushed westward for the last drive into Havana as the battle dragged on. Guevara started on an arduous 7-week march on foot, only travelling at night to escape the ambush and often going without food for several days. Guevara's aim in the final days of December 1958 was to divide the island in two by seizing Las Villas province. He completed a succession of "great tactical wins" in a few days, giving him control of everything except the province's capital city of Santa Clara. Following that, Guevara led his "death squad" in the attack on Santa Clara, which proved to be the revolution's final decisive military victory. During the six weeks preceding up to the fight, his forces were utterly encircled, outgunned, and overpowered. Some analysts consider Che's final triumph, despite being outnumbered 10:1, to be an "extraordinary tour de force in contemporary warfare." This contrasted claims by the severely censored national news media, which had announced Guevara's death during the combat at one point. Che also began writing his book Guerrilla Warfare while recuperating at Tarara. In February, the revolutionary leadership designated Guevara "a Cuban citizen by birth" in recognition of his role in the victory. Guevara notified Hilda Gadea of his new girlfriend when she arrived in Cuba in late January, and the two agreed to divorce on May 22. On July 26, 1958, he married Aleida March, a Cuban-born member of the 26 July movement with whom he had been living since late 1958. In June, Guevara returned to Tarara, a coastal town, for his honeymoon with Aleida. Guevara has a total of five children from his two marriages. The Congo, Bolivia, and the Death of Che GuevaraGuevara travelled to New York City in December 1964, where he spoke to the United Nations General Assembly about US intervention in Cuban affairs and incursions into Cuban airspace. Back in Cuba, disillusioned with the direction of the Cuban social experiment and its reliance on the Soviets, Guevara began to concentrate his efforts on fostering revolution elsewhere. He disappeared from the public space after April 1965. For the next two years, his movements and whereabouts remained unknown. Later, it was discovered that he had travelled to what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo with other Cuban guerrilla fighters in a futile attempt to assist the Patrice Lumumba Battalion, which was fighting a civil war there. During that time, Guevara resigned from his position as a minister in the Cuban government and renounced his Cuban citizenship. After his efforts in the Congo failed, he fled to Tanzania and then to a safe house in a village near Prague. Guevara travelled to Bolivia incognito (beardless and bald) in the autumn of 1966 to form and lead a guerrilla group in the Santa Cruz region. Following some early victories, Guevara and his guerrilla group found themselves constantly on the run from the Bolivian army. On October 8, 1967, a special detachment of the Bolivian army aided by CIA advisers nearly annihilated the group. Guevara, who had been wounded in the attack, was apprehended and shot. His hands were severed before his body was secretly buried, and they were preserved in formaldehyde so that his fingerprints could be used to confirm his identity. Jon Lee Anderson, one of Guevara's biographers, announced in 1995 that he had learned Guevara and several of his comrades had been buried in a mass grave near the town of Vallegrande in central Bolivia. On the 30th anniversary of Guevara's death, a skeleton believed to be his, and the remains of his six comrades were disinterred and transported to Cuba to be interred in a massive memorial and monument in Santa Clara. On the 80th anniversary of his birth, a statue dedicated to Guevara was dedicated in his hometown of Rosario, Argentina, in 2008, following decades of acrimonious debate among its citizens over his legacy. A French and a Spanish journalist argued in 2007 that the body brought to Cuba was not Guevara's. The Cuban government denied the claim, citing scientific evidence (including dental structure) from 1997 as proof that the remains were those of Che Guevara.

Next TopicKanye West

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share