SnakebiteSnakebite is an injury caused by the bite of a venomous snake. A common sign of a bite from a venomous snake is the presence of two puncture wounds. This may result in swelling, redness, and severe pain in the area, which may take up to an hour to appear. The venom may cause kidney failure, bleeding, tissue death around the bite, allergic reaction, breathing problems, etc. Bites may result in the loss of a limb or other chronic problems or depend on the type of snake, the bitten area, the amount of venom injected, and the person's general health bitten. Problems are more severe in children than adults due to their smaller size. Snakes administer bites, both as a method of hunting and as a means of protection. Risk factors for bites include working outside with one's hands, such as farming, forestry, and construction. Snakes commonly involved in poisonings include vipers, sea snakes, and elapids such as cobras, mambas, and kraits. The majority of snake species do not have venom and kill their prey by squeezing them. Venomous snakes can be found on every continent except Antarctica. Determining the type of snake that caused a bite is not possible. WHO says snakebites are a neglected public health issue in many tropical and subtropical countries. Wearing protective footwear, avoiding areas where snakes live, and not handling snakes can prevent snakebites. Treatment depends on the type of snake but washing the wound with soap and water and holding the limb can be a first aid treatment for all snake bites. Trying to suck out the venom, cutting the wound with a knife, or to use a tourniquet, is very harmful. Antivenom is effective at preventing death from bites, but antivenoms have side effects as well. The type of antivenom depends on the type of snake involved. When the type of snake is unknown, antivenom is given according to the types known to be in that area. The number of venomous snakebites that occur each year may be as high as five million. They result in about 2.5 million poisonings and 20,000 to 125,000 deaths. The frequency and severity of bites vary greatly among different parts of the world. They occur most commonly in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and rural areas more greatly affected. Snakebite SymptomsMostly two types of snakes are there, venomous and non-venomous. In the U.S., all of the venomous snakes, except for the coral snake and pit vipers. Pit vipers are distinguishable by a noticeable depression between the eye and nostril. This pit is the heat-sensing area for the snake. While all pit vipers have a triangular head, not all snakes with a triangular head are venomous. To identify a snake bite, below are the following general symptoms:

Dry snakebites and those inflicted by a non-venomous species may still cause severe injury. The bite may become infected from the snake's saliva. Infection is often reported from vipers' bites, whose fangs can deep puncture wounds, introducing infectious organisms into the tissue. Most snakebite, from either a venomous or a non-venomous snake, will have some local effect. Minor pain and redness occur in over 90 percent of cases. Bites by a viper and some cobras may be extremely painful, with the local tissue sometimes becoming tender and severely swollen within five minutes. This area may also bleed, blister, and may lead to tissue necrosis. Bites by some snakes, such as the coral snake, kraits, Mojave rattlesnake, and speckled rattlesnake, may cause little or no pain, despite their serious and potentially life-threatening venom. Some people experience a rubbery, minty, or metallic taste after being bitten by certain rattlesnake species. Spitting cobras and rinkhalses can spit venom in a person's eyes. This results in immediate pain, ophthalmoparesis, and sometimes blindness. CauseMost snakebite occurs in the developing world in those who work outside, such as hunters, farmers, and fishers. It happened when a person steps on the snake or approaches it too closely. In the US and Europe, snakebites commonly occur in those who keep them as pets. The type of snake that most often delivers serious bites depends on the region of the world. In North America, rattlesnakes are the primary concern and up to 95% of all snakebite-related deaths. In the United States are attributed to the eastern, western and eastern diamondback rattlesnakes. In South Asia, it was previously believed that kraits, Russell's viper, carpet vipers, and cobras were the most dangerous from other snakes. However, they may also cause significant problems in this area of the world. Snake VenomSnake venom is produced in modified parotid glands, which are responsible for secreting saliva. It is stored in structures called alveoli behind the animal's eyes and ejected voluntarily through its hollow tubular fangs. Venom is composed of hundreds to thousands of different proteins and enzymes, all serving various purposes, such as interfering with a prey's cardiac system or increasing tissue permeability so that venom is absorbed faster. The venom affects virtually every organ system in the human body. It can be a combination of many toxins, including hemotoxins, myotoxins, neurotoxins, and cytotoxins, allowing for an enormous variety of symptoms. Earlier, the venom of a particular snake was considered one kind only, i.e., either hemotoxic or neurotoxic. Although there is much known about the protein compositions of venoms from Asian and American snakes, comparatively little is known about Australian snakes. The strength of venom differs markedly between species and even more so between families, as measured by median lethal dose (LD50) in mice. Subcutaneous LD50 varies by over 140-fold within elapids and by more than 100-fold in vipers. The amount of venom produced also differs among species, with the Gaboon viper can potentially deliver from 450-600 milligrams of venom in a single bite, the most of any snake. Opisthoglyphous colubrids have venom ranging from life-threatening to barely noticeable. PreventionSnakes are most likely to bite when they feel threatened, are startled, are provoked, or when they have been cornered. Snakes are likely to approach residential areas when attracted by prey. When in the wilderness, treading heavily creates ground vibrations and noise, which will often cause snakes to flee from the area. However, this generally only applies to vipers, as some larger and more aggressive snakes in other parts of the world will respond more aggressively.

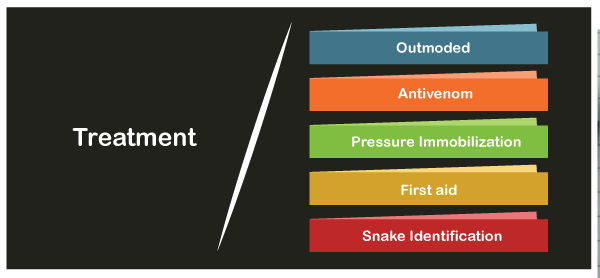

TreatmentIt may be difficult to determine if a bite by any species of snake is life-threatening. A bite by a North American copperhead on the ankle is usually a moderate injury to a healthy adult, but a bite to a child's abdomen or face by the same snake may be fatal. The outcome of all snakebites depends on many factors, such as:

The most important thing to do for a snake bite is to get emergency medical help as soon as possible, such as: 1. Snake identificationIdentification of the snake is important in planning treatment in certain areas of the world, but it is not always possible. Ideally, the dead snake would be brought in with the person, but in areas where snake bite is more common, local knowledge may be sufficient to recognize the snake. However, in regions where polyvalent antivenoms are available, such as North America, snake identification is not a high priority item. Attempting to catch or kill the offending snake also puts one at risk for re-envenomation or creating a second person bitten, and generally is not recommended. The three types of venomous snakes that cause the most major clinical problems are cobras, vipers, and kraits. A scoring system can determine the biting snake based on clinical features, but these scoring systems are extremely specific to particular geographical areas. 2. First aidSnakebite first aid recommendations vary because different snakes have different types of venom. Some have a little local effect but life-threatening systemic effects, in which case containing the venom in the bite's region by pressure immobilization is desirable. Other venoms instigate localized tissue damage around the bitten area, and immobilization may increase the severity of the damage in this area and reduce the total area affected. Many organizations, including the American Red Cross and American Medical Association, recommend washing the bite with soap and water. Australian recommendations for snakebite treatment:

3. Pressure immobilizationClinical evidence for pressure immobilization via the use of an elastic bandage is limited. It is recommended for snakebites that have occurred in Australia. The British military recommends pressure immobilization in all cases where the type of snake is unknown. The object of pressure immobilization is to contain venom within a bitten limb and prevent it from moving through the vital organs' lymphatic system. This therapy has two components, such as:

4. AntivenomUntil the advent of antivenom, bites from some species of snake were almost universally fatal. Despite huge advances in emergency therapy, antivenom is often still the only effective treatment for envenomation. Antivenom is injected into the person intravenously and works by binding to and neutralizing venom enzymes. It cannot undo the damage already caused by venom, so antivenom treatment should be sought as soon as possible. Modern antivenoms are usually polyvalent, making them effective against the venom of numerous snake species. Pharmaceutical companies that produce antivenom target their products against the species native to a particular area. Although some people may develop serious adverse reactions to antivenom, such as anaphylaxis, this is usually treatable in emergencies. Hence, the benefit outweighs the potential consequences of not using antivenom. 5. OutmodedThe following treatments are considered no use or harmful, including tourniquets, incisions, suction, cold, and electricity application. Cases in which these treatments appear to work may be the result of dry bites.

All of these misguided attempts at treatment have resulted in injuries far worse than an otherwise mild to moderate snakebite. In worst-case scenarios, thoroughly constricting tourniquets have been applied to bitten limbs, completely shutting off blood flow to the area.

Next TopicWhat is Solidification

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share