Difference Between Innate and Adaptive ImmunityBacteria and viral pathogens can invade our bodies and cause infections and diseases. Our body must be strong enough to protect us from these invaders by fighting them. This protection is conferred by the immune system, a special system of the body that works through various pathways to protect the body from infections. The two most important pathways through which the immune system works are innate immunity and adaptive immunity. In this article, we will explore how the immune system works and the difference between the different types of immunity provided by our immune system.

The ability to ward off infections by fighting foreign disease-causing agents is called immunity. The foreign agent can be any organism that is not recognized as a part of the body, such as a pathogen or a toxin. Each human being has a special type of surface molecule called the histocompatibility complex class I, which works by identifying the body molecules as the body's and giving those molecules a self-tag. Any other molecule that is not tagged as self is considered foreign and recognized by the immune system to be targeted. The immune system is activated when such molecules enter the body through a special trigger called antigens. When a person is born, a certain type of immunity is present in their body. This immunity, which has not been acquired but has always been there in the body, is called innate immunity. It is a natural immunity governed by the genetic structure of an organism and is always present until the person's death. According to the evolutionary perspective, innate immunity is a primitive type of immunity found not only in humans and vertebrates but also in many plants, insects, and fungi. As this type of immunity has been present since birth, it is not specific, but it has a similar mechanism of defence for different invaders, and the response is quite fast. In humans, the first line of defence is provided by innate immunity by encompassing physical and chemical barriers. The second line of defence is based on cellular and humoral aspects.

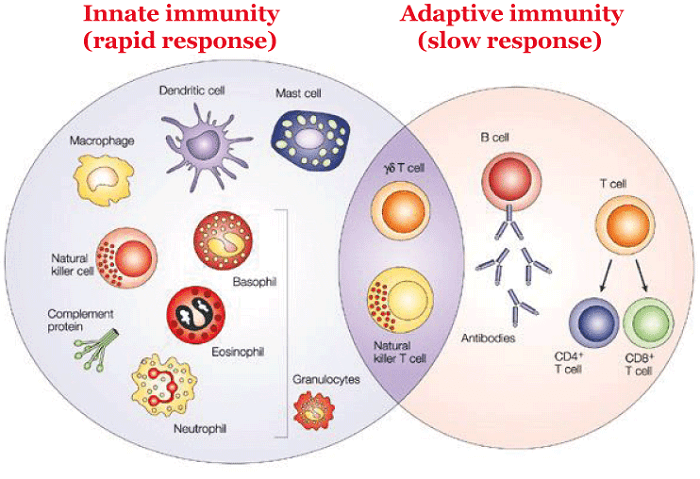

The path taken by the immune system to fight against the invaders ultimately depends on the threat's location, whether it is intracellular or extracellular. Intracellular invaders are mostly viruses, and extracellular invaders are mostly bacteria. The innate immune system recognizes bacteria or viruses due to the absence of tags given by MHC-class I molecules. The other way to recognize a foreign pathogen inside the body is through some common patterns that are common to the pathogen family but absent in the host. These patterns are called pathogen-associated molecular patterns or PAMPs. Recognition of these patterns is followed by their destruction by the host's killing system, which includes phagocytosis and cytotoxic killing. In case of intracellular threats, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize non-self-components like intermediate products, viral DNA or viral RNA. This recognition triggers a cascade of reactions leading to the production of certain compounds like anti-inflammatory cytokines that signal infected cells to undergo apoptosis. The innate immune system then destroys the flagged cells to avoid further infection in the body. The role of the innate immune system in conferring immunity can be summarized as follows: (1) physical and chemical barriers being the first line of defence that protects the body from pathogens; (2) prevention of infection through humoral-mediated processes like complement cascade; (3) removal of non-self cells through phagocytosis; and (4) preparation of the body for future attacks by activating the adaptive immune system. Adaptive immunity is a type of immunity that is not imprinted in the genome of the organism and is developed over time due to a particular incidence. This type of immunity is not present at birth like innate immunity. When the body faces an invasion of specific invaders, they release its antibodies. The body encounters these antibodies and develops adaptive immunity to prevent further infections from the same type of antigens. Adaptive immunity can be developed in an individual artificially by vaccination, where dead antigens are introduced into the body, which the body recognizes as foreign antigens. A person also develops adaptive immunity naturally when they suffer from any disease or infection. Adaptive immunity is also called acquired immunity because it is not found naturally at birth but is acquired or developed as a result of exposure to antigens. Compared to the innate response, adaptive immunity gives a slower response. The primary immune response depends on the type of antigen present and helps the body to remember this encounter as a memory for future reference. The memory of an adaptive response is not temporary and remains with the organism throughout its lifetime. The adaptive immune system is activated via signalling molecules and/or the presentation of antigens by antigen-presenting cells. T cells perform a variety of tasks, including the direct destruction of infected cells and aiding in the stimulation of B cells to produce antibodies. Naive B cells differentiate into memory cells and plasma cells after being activated. Plasma cells continue to manufacture and secrete huge amounts of antigen-specific antibodies to aid in neutralizing and eliminating their target. Memory cells can survive for decades and reactivate to make antibodies when their target antigen is present, resulting in a quicker and stronger reaction to repeated exposures. The cells that participate in the innate immune response include myeloid-derived macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and dendritic cells. Natural killer cells are also a part of the innate immune system, but they are produced from lymphoid stem cells. The cells that participate in the adaptive immune response include B cells that differentiate into memory and plasma cells and a variety of T cells, including T helper cells and cytotoxic T cells. Natural killer T cells and gamma-delta T cells are present in both innate and adaptive immunity. The immune system's ability to react more quickly and efficiently to a pathogen that has already been exposed to it is called immunological memory. This ability includes all antigens, not only those from viruses, and is owed to memory B cells. Immunological memory helps to immunize against infectious diseases and prevent contracting them naturally. The body can fight off a virus more swiftly if it comes into contact with it again after developing the antibodies required to do so, whether the memory cells were created as a result of an infection or a vaccination that exposed them to weak, dead, or antigen components. Innate immunity is non-specific and present at birth, while adaptive immunity is specific and develops over time. The two types of immunity differ in how they respond to foreign invaders and how they work to protect the body. Key DifferencesThe immune system is the body's natural defence mechanism that helps protect us against harmful pathogens and disease-causing agents. There are two types of immunity that work together to keep us healthy: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. While both types of immunity are important, they differ in how they respond to foreign invaders and how they work to protect the body. Innate immunity is non-specific and present at birth, while adaptive immunity is acquired and specific to particular pathogens. Innate immunity responds quickly to pathogens by recognizing common patterns, while adaptive immunity takes longer to develop but provides a more targeted response. Innate immunity does not involve the production of antibodies, while adaptive immunity relies on the production of antibodies to fight pathogens. Innate immunity does not develop memory, while adaptive immunity "remembers" previous infections, allowing for a faster response if the same pathogen is encountered again. ConclusionInnate and adaptive immunity are both crucial components of the immune system, working together to protect the body from harmful pathogens. While innate immunity provides a rapid response to a wide range of pathogens, adaptive immunity provides a more targeted response that develops over time and "remembers" previous infections. Understanding the differences between these two types of immunity can help us appreciate the complexity of the immune system and how it works to keep us healthy.

Next TopicDifference between

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share