Epithalamion SummaryIntroductionEdmund Spenser composed an ode called Epithalamion for his bride, Elizabeth Boyle on their wedding day in 1594. In 1595, William Ponsonby published it for the first time in London as a chapter in a book named Amoretti and Epithalamion. Epithalamia, which means "to the bridal chamber" in Greek, are poems or musical compositions that honor marriage.

Except for the fifteenth stanza, Epithalamion has a rhyming system of ABABCC, DEDEFF, etc. Each of the 24 stanzas contains 18 or 19 lines, except the fifteenth, which has 17 lines. The final stanza is a 7-line emissary, a brief formal stanza that serves as the poem's epilogue. Overall, there are 433 lines in the poem. The poem's 24 stanzas correspond to the hours of Midsummer Day, as Spenser methodically describes the hours of the day from early in the morning to late into the wedding night. The ode's content shifts from youthful exuberance to middle-aged worries by starting with lofty expectations for a happy day and finishing with an eye toward the speaker's legacy to future generations. About the PoetEdmund Spenser's birth was probably in or around 1552 and occurred in East Smithfield, London. However, there is significant debate regarding his actual birth year. He was a member of the Merchant Taylors' Company and the offspring of obscure clothiers John Spenser and Elizabeth, who are both almost unknown. John Spenser was the father of the family.

He is best known for his epic poem The Faerie Queene, a magical allegory honoring Elizabeth I and the Tudor dynasty. He is frequently regarded as one of the greatest English-language poets and is acknowledged as one of the foremost artisans of emerging Modern English verse. He passed away on January 13, 1599, most likely from an illness brought on by fatigue. He was laid to rest shortly after in the Poets' Corner in the south transept of Westminster Abbey. SummaryThis ode opens with an invocation to the Muses, as is customary in works with classical influences. However, in this instance, their assistance is needed to help the husband awaken his bride rather than to produce a literary work. The bride is then confronted by an increasing number of figures who try to remove her from her bed. The bride finally awakes when the sun rises and starts going to the wedding pavilion. She goes to the "temple" (the church sanctuary where she will be legally wed to the groom), gets married, and then a party follows. Immediately, the groom wants everyone to go and the day to end so that he can relish the bliss of his wedding night. Once night falls, though, the groom shifts his attention to the offspring of their union and prays to numerous gods that his new wife's womb will be fertile and bear him many children. Spenser is highly systematic in how he portrays time passing, both in the chronological and subjective sense of time experienced by those anxiously or fearfully waiting. In the first stanza, the bridegroom asks the muses for guidance so that he might appropriately sing the praises of his loving bride. He says he's going to sing to himself. Unlike many other poets who only invoked one muse, Spenser invokes all the muses in this poem, suggesting that his subject demands the complete gamut of legendary inspiration. The allusion to Orpheus is a nod to that mythological figure's ability to entice his wife's spirit from the afterlife with the help of his lovely music; the groom similarly aspires to rouse his bride from her sleep and usher her into the light of their wedding day. This stanza concludes with the same refrain as most subsequent stanzas. In the second stanza, the bridegroom calls the muses to his beloved's bower before dawn to awaken her. The God of marriage, Hymen, is already awake, and the bride should be too. The bride's wedding day is today, and the groom implores the muses to remind his wife of this happy occasion. The poet refers to Hymen, another legendary figure. He wants to convey that if the bride and the groom are ready for marriage, his wife should also be prepared. The significance of the wedding day is emphasized, which ought to persuade the bride to show up as soon as possible. The marriage ceremony, not the bride, decides what is required. In the third stanza, the bridegroom commands the muses to gather as many nymphs as possible in the bridal chamber. They are instructed to gather as many fragrant flowers as possible along the road to decorate the path leading from the "bridal bower," where the wedding ceremony will occur, to the bride's rooms. If they do, she will rely exclusively on flowers from her lodging to the wedding venue, and the bride will be awakened by their song as they flower-decorate her doorstep. Greek mythology is deeply ingrained in this celebration of Christian marriage. There is no more paganist image than these nature spirits scattering various flowers around the ground to provide a lovely pathway from the bride's bedroom to the wedding pavilion. In the fourth stanza, to have the perfect wedding, the groom addresses the countless nymphs of other natural settings and demands that they take care of their area of expertise. The nymphs who care for the ponds and lakes should ensure the water is clear and devoid of alive fish so they may see their reflections in it and thus best prepare themselves to be viewed by the bride. On her wedding day, the bride should be protected from wolves by the same mountain and forest nymphs who protect the deer from wolves' ravenous attention. Both groups are anticipated to participate in enhancing the wedding site with their beauty. By stating this, Spenser elaborates on the summoning of a nymph from Stanza 3. He may have expected some disaster to visit the wedding because he stresses the two parties' ability to avoid the commotion. In the fifth stanza, the groom tells his bride to wake her. The sun god Phoebus is showing off "his glorious hed" after the sunrise has departed. The groom contends that the birds' merry song is an exuberant welcome to the bride. To maintain the ode's classical theme, the fabled figures of Rosy Dawn, Tithones, and Phoebus are mentioned in this stanza. So far, it has a message identical to a pagan wedding hymn. The fact that the groom must speak directly to his wife highlights his impatience and the futility of relying on the muses and nymphs to bring the bride. In the sixth stanza, now that the bride has awakened, her eyes have been compared to the sun because they are "goodly beams/More bright than Hesperus." In addition to the Hours of Day and Night, the Seasons, and the "three handmayds" of Venus, the groom also asks the "daughters of delight" to attend to the bride. He encourages the latter to sing to his bride as she prepares for the wedding, just like they do for Venus. Here, a second dawn occurs when the bride's "darksome cloud" is removed, allowing her eyes to shine with all their brilliance in this stanza. The nymphs?the "daughters of delight"?are still urged to attend the wedding, but Spenser also introduces the personifications of time, represented by the hours that make up Day, Night, and the seasons. It is important to note that, in this passage, he sees time itself as participating in the marriage ceremony just as much as the nymphs and handmaids of Venus. He will return to this time motif later. In the seventh stanza, now that the bride and her attendant virgins are ready, it's time for the groom's men and the groom to get ready. To protect his bride's light skin from burning, the husband begs for the sun to shine brilliantly but not intensely. Then he begs Phoebus, the creator of the arts and the sun god, to grant him this day of the year while keeping the others for himself. He offers to trade his poems in exchange for this enormous favor. In this paragraph, as the groom addresses Phoebus, the subject of light as a symbol of joy and a representation of artistic ability starts to take shape. Spenser refers to his poetry once more as an honorable sacrifice to the God of literature and the arts, which, in his opinion, has won him the goodwill to have this one day belong to him rather than the sun god.

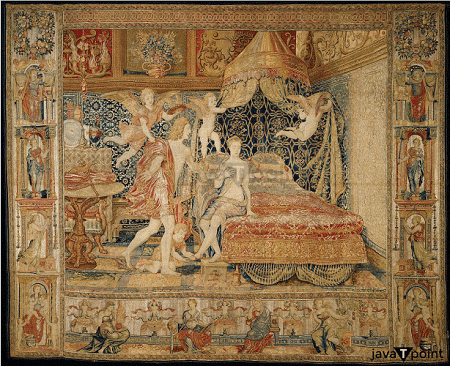

In the eighth stanza, the entertainment and guests from the mortal wedding begin. Women dance and play their timbrels while the minstrels perform their music. The wedding hymn "Hymen io Hymen, Hymen" is sung loudly by young lads as they race through the streets. People who hear the cries cheer the lads and sing along with them. Here, Spenser turns his attention to the wedding ceremony attendees, the entertainment, and potential visitors. He describes a typical Elizabethan wedding with all of the classically inspired details. In the ninth stanza, when the bridegroom sees her coming, he compares her to a white-clad Phoebe, another name for Artemis, the goddess of the moon. She looks more like an angel to him because of how appropriate her white clothing is. She shyly avoids the admirers' eyes and flushes at the choruses of adulation she is hearing. This unique stanza contains a "missing line," a break after the ninth line. The organization of Spenser's lines and meter, which mathematically precisely repeat the hours of the day, is likely aided by the structure. The gap occurs three lines before the verses that describe the bride's response to her suitors. Therefore, there is no artistic justification for it in the stanza. The groom essentially agreed two stanzas ago to take Phoebus' position of prominence on this day. Therefore, the comparison to Phoebe, Phoebus' twin sister, is crucial. This day, when Day and Night are inevitably bound by the passage of time, he sees the bride as a perfect, even heavenly, counterpart to himself. In the tenth stanza, the bridegroom inquires the women if they have ever seen somebody in their town who is as stunning as his bride after they see her. Then he lists all her good qualities, beginning with her eyes and eventually covering her entire body. The bride's breath-taking beauty prompts the maidens to stop singing and gaze at her. By doing this, Spenser uses the Blason convention, where a woman's physical characteristics are singled out and metaphorically depicted. Her cheeks and lips are compared to fruit (apples and cherries), her cheeks and forehead are described as valuable objects (sapphires and ivory), her eyes and forehead as precious gems, her breast as a bowl of cream, her nipples as lily buds, her neck as an ivory tower, and her entire body as a lovely palace. In the eleventh stanza, the groom shifts from the bride's exterior beauty to her spiritual elegance, which he claims to notice better than anybody else. He compliments her for having a positive attitude, sweet love, purity, religion, dignity, and humility. He maintains that if her admirers could only perceive her inner beauty, they would be considerably more in awe of it than they now are. He paints a picture of the ideal woman, free from flaws or wandering thoughts, while describing his bride. If the guests could only see her genuine beauty?her flawless beauty?they would be as stunned as those who witnessed "Medusa's mazeful hed" and were afterward turned to stone. In the twelfth stanza, the bridegroom requests that the temple's doors be unlocked so she may enter and bow before the altar. Since his bride enters this sacred site with respect and humility, he presents her as an example for the onlooker maidens to imitate. Instead of referring to Hymen or Phoebus, the bride advances "before th' almighties view." In the thirteenth stanza, the poem focuses on the bride's response to the priest's blessing and the groom's response to his bride's response, which is now firmly established in the Christian wedding rite. The priest blesses the bride and the marriage as she stands at the altar. The bride asks why she should blush to give the groom her hand in marriage. She blushes, making the angels forget their duties and surround her. In the fourteenth stanza, after the Christian portion of the wedding ceremony, the groom requests that the bride be taken home again so that the festivities can begin. By focusing on the "God Bacchus," Hymen, and the Graces rather than the "almighty" God of the church, he calls for feasting and drinking. Perhaps as a response to his earlier imprecation to Phoebus that this day belonged to him alone, he views this day as holy for himself.

In the fifteenth stanza, Spenser allows the reader to place this poetic account of the ceremony in a legitimate, historical setting. The ringing bells prompt the groom to declare the day holy and invite everyone to the celebration. When he realizes that his wedding is taking place on the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, he switches his tone from exultation to remorse. As a result, his nocturnal nuptial joy will be postponed even more, but only briefly. In the sixteenth stanza, again concentrating on the passage of time, the speaker can find encouragement in the approaching dusk. He asks the evening star to direct the bride and groom to their bedroom since he is eager to spend time alone with his bride. In the seventeenth stanza, the bride is taken to her bed by her husband as the singers and dancers leave the wedding. He compares the sight of his fianc�e lying in bed to that of Maia, the mountain goddess with whom Zeus had Hermes, and expresses his desire to spend time alone with her. In the eighteenth stanza, finally, night has arrived, and the groom asks that it cover and guard them. Once more, Spenser references Zeus in a classical context by naming the lady and children of Zeus' interactions with her. The prospective kid that might be born of this union has almost completely taken the bride's place or the act of consummation. In the nineteenth stanza, when the bride and groom are finally by themselves, the speaker suddenly launches into a list of anxieties that borders on the ridiculous. The bridegroom asks God to protect the newlyweds from evil spirits or negative thoughts tonight. The entire stanza lists potential threats that he begs the reader to ignore. In the twentieth stanza, resuming his enjoyment of his beloved bride, the poet calls for the "sonnes of Venus" to play all night long. Even though he knows that sleep can and must come at some point, he wishes to savor these "little loves" as much as possible with his wife. In the twenty-first stanza, Spenser continues to address Cinthia, the moon, in his prayer for his wife's pregnancy. He implores her to reflect on her adoration of Endymion, the "Latin Shephard," a relationship that finally gave birth to fifty daughters or the moon's phases. He explicitly requests that she create a fertile "chaste womb" for his bride this evening.' In the twenty-second stanza, the bridegroom expands the gods on his patron's list. He calls on Juno, the goddess of marriage and wife of Zeus, to make their union enduring and revered before turning her focus to ensuring its success. He also requests the same from Hebe and Hymen on their behalf. The speaker does return to the hope or prayer that the union will remain pure, but he still regards conception as the most important thing that needs to happen that night. In the twenty-third stanza, Spenser calls on all the gods in the skies to testify and bless the marriage, bringing this ode to a dramatic conclusion. In no uncertain terms, he declares that the blessing he would most like to experience is offspring; he has no other wish but to bear a kid from this relationship. Then he tells his wife to relax in anticipation of becoming a mother and father. In the poem's last stanza, Spenser returns to a self-conscious reflection on his ode, following Elizabeth's tradition. The bride, he believes, needs numerous bodily adornments as well, so the groom addresses his song with the obligation to be a "goodly ornament" for her. He requests that this ode, which he is forced to provide in place of the numerous ornaments his bride ought to have, become an even greater ornament for her. The groom thinks his ode would serve as an "endlesse moniment" to his sweetheart because he didn't have enough time to buy her these external decorations. ConclusionTo sum up, Edmund Spenser's "Epithalamion" is a great ode to marriage and love that displays the poet's extraordinary brilliance and expertise. Spenser takes us on a trip that celebrates the happiness and beauty found in the marriage of two souls through his lyrical and impassioned verses. The course of the wedding day is reflected in the poem's structure and form, which starts with a sense of expectancy and builds to a symphony of love and joy. The reader is transported into a world of heightened emotions where the beauty of nature and the strength of love are intertwined by Spenser's excellent use of imagery, symbolism, and vivid descriptions. "Epithalamion" also examines the transforming power of love. Spenser portrays love as a power that can transcend space and time and uplift the human spirit. The speaker develops a strong sense of togetherness with his beloved via love, forging a material and spiritual connection. The poem is a monument to the enduring strength of love and how it can lead to contentment and happiness. Additionally, "Epithalamion" reveals Spenser's profound comprehension of the subtleties of emotional complexity. The joy and fragility that come with love are both depicted by him, and he acknowledges that the road to love is not always easy. The poem captures the realities of relationships by addressing the difficulties and roadblocks that partners may encounter. However, love's triumph and final recompense are emphasized, demonstrating Spenser's eternal optimism. Overall, "Epithalamion" is a classic work of literature that never fails to enthrall readers with its lyrical beauty, deep insights, and celebration of love.

Next TopicEverything I Never Told You Summary

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share