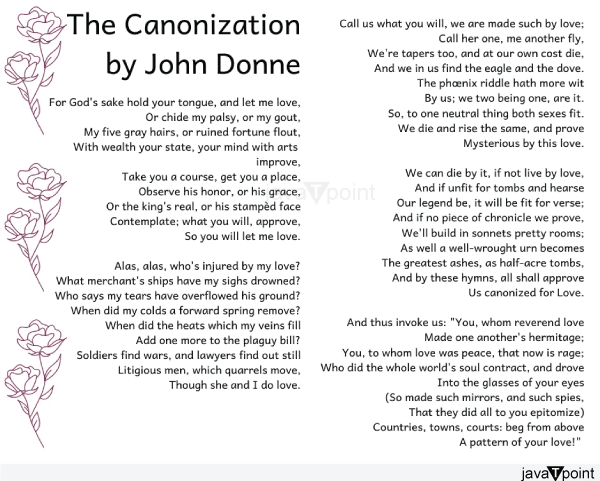

The Canonization SummaryJohn Donne's posthumous collection of Songs and Sonnets included The Canonization, which was originally published in 1633. There are groups of nine lines inside each of the poem's five stanzas. From stanza to stanza, the poet alternates the lines' rhyme schemes, which follow the pattern abbacccaa. Donne needed to be more reliable when it came to the metre. Iambic pentameter is used sporadically throughout the text. Thus, there are five sets of two lines in each of the lines. Unlike the second, the first of them is not emphasised. Other verses by Donne are written in iambic tetrameter, which means that instead of five beats for each line, there are four groups of two. The reader should note the last line of each stanza. In this instance, iambic trimeter, or a line with three groups of two beats, is what Donne is using. The employment of an elaborate metaphor known as a conceit is among "The Canonization's" most significant features. It may be difficult and rare to use a metaphor like this. A metaphor equating the speaker and his sweetheart to a phoenix is introduced in the last stanza. They may live in this form, pass away in a blaze of desire, and then resurrect to live even more exquisitely. The word "death" may also be used to describe the peak of a sexual relationship, making this a double allusion. About The AuthorBorn from a family of recusants, John Donne was an English poet, scholar, soldier, and secretary who died on March 31, 1631. He eventually joined the Church of England as a clergyman. He was appointed Dean of London's St. Paul's Cathedral (1621-1631) with the support of the monarch. In terms of poets who write on metaphysics, he is recognised as their leading representative. His poetical works are recognised for their symbolic and sensual manner, and they include sonnets, love poems, religious poetry, Latin translations, epigrams, elegies, lullabies, and satires. His sermons are another thing that is highly renowned.

The abrupt beginnings, many contradictions, ironies, and dislocations that define Donne's style. Along with his frequent dramatic or daily speech rhythms, strong syntax, and rough eloquence, these characteristics were a response against the smoothness of traditional Elizabethan poetry as well as an adaption of European baroque and mannerist methods into English. Early in his career, he wrote poems that demonstrated a deep understanding of English culture. True religion is a significant issue in Donne's poetry as well. He gave it a lot of thought and often theorised about it. He also penned sexual and romantic poetry as well as secular poems. He is renowned in particular for his mastery of philosophical pretensions.Despite having a brilliant education and literary genius, Donne spent many years in poverty while mainly dependent on his affluent acquaintances. He devoted a large portion of the money he inherited to womanizing, reading, leisure activities, and travel during and after his studies. Donne and Anne More had twelve children together after a covert marriage in 1601. Although he did not wish to accept holy orders and only did so because the king commanded it, he was ordained as an Anglican deacon in 1615 and subsequently as a priest in 1616. In 1601 and 1614, he served as a member of the legislature. Theme of the Poem"The Canonization" makes the case that love is a serious, enduring, and even sacred energy rather than merely a frivolous game for kids to enjoy. The poem's speaker, a middle-aged guy, tells a buddy to stop making fun of him for his later-in-life relationship and to let him be in love already within the first couple of stanzas. He maintains that love is much more than a childish emotional whirlwind. True lovers are "canonized" by their love since it has a powerful, transformational, and purifying force. In other words, love has the power to transform ordinary people into saints who are completely committed to a holy mission. According to the speaker of the poem, it is a common misconception that love is only for the impressionable, naive, and young. The speaker responds that his love doesn't hurt anybody when his buddy makes fun of him for falling in love at an old age when he has "grey hairs" and achy joints. This shows that he has a reasonable understanding of what love is like. He makes fun of the cliched love poetry that claims love can alter the world, saying his "sighs" and "tears" haven't sunk a single ship or "overflowed" a single field (and that his buddy should leave him alone since his love isn't bothering anybody). The speaker's rejection of overused clich�s shows that he is an expert on love and knows both what it is and is not. "The Canonization" portrays love as a strong, even divine power. Despite the magnificence of love, the speaker is aware that it isn't often memorialized in books or monuments the same way that, for instance, memories of war or politics are (perhaps because they're just too intimate). The speaker of the poem muses that the best way to commemorate a great love isn't even with a large stone monument. According to this poem, poetry is the only medium that can accurately portray and maintain genuine love's power. Poetry is required to create the monument that true love so richly deserves. The speaker notes that not all love tales end up in the "chronicles" (or history books) since love is too intimate and personal to be a topic of the historical record. Nobody creates a "well-wrought urn" (a fancy burial vase) or carves a love tale into the side of a "tomb" to store their loved one's ashes. Great warriors, leaders, and artists are memorialized in stone, but great lovers don't get those types of honors; monuments like this are only built in honor of persons who carried out publicly heroic deeds. Summary of the PoemStanza 1: The poet requests that his buddy refrains from speaking up when he attempts to talk him out of having sex and let him go on with his love without any interference. In the same way that it is pointless for him to criticize the poet for having conditions like paralysis or gout or for having baldness or ailments like old age or his misfortune, so too is it pointless for him to attempt to stop the poet from having a sexual relationship. Instead, then spending time giving the poet advice, it would be preferable for him to advance his status by accumulating cash, growing his intellect through learning, or discovering a passion for the arts. He may enroll in the course of study or get a job at court, giving him the opportunity to see the king's dignity and elegance in action. As a courtier, he will get to view the king's real face (his true colors), or he may decide to go into business, earn money, and then see the king's likeness imprinted on coins. Whatever he chooses to do, he must refrain from interfering with the poet while he makes love to his sweetheart. Stanza 2: But his creation of love injures no one. His laments haven't sunk a single cargo ship. The coldness of his concerns did not lengthen the winter or postpone the arrival of spring, and neither did his tears generate any floods. His devotion did not increase the number of people who died from the disease. While the attorneys are engaged in court cases, the troops are still engaged in combat. Why should anybody object to his making of love since the world continues to function normally in spite of his love? Stanza 3: The poet and his love will be called by the buddy anything he wishes (crazy or humorous), but whatever they are, is the outcome of their making love. The poet's acquaintance may refer to him or her as a fly, and the poet's adored as another fly rushing after the light. He might have called them candles since they both burn out from love for one another. Due to their similarity in being both fierce and delicate predators, the eagle and the dove, he may draw comparisons between them. The poet and his sweetheart may be described in terms of the Phoenix tale. Their two sexes blend together so well that they create a creature that is unisex; as a result, they resurrect after passing away in exactly the same shape as before, much as the Phoenix does after rising from its own ashes. Their love enigma will be revered, much like the Phoenix's secret. Stanza 4: The lovers may at least die for their love if they are unable to get immortality via it. Although the tale of their love may not be worthy of monuments and graves, it is at least suitable as poetry's subject matter. Although their love may not have been documented in books of history, sonnets and song lyrics will undoubtedly refer to it. The world will revere them as canonized lovers (saintly lovers), just as famous men's ashes are kept in decorative urns or tombs spanning half an acre. They will be canonized for the sake of love in the same manner that saints were declared holy for the love of God. Their devotion is sincere and unselfish. Analysis of the Poem

In "The Canonization," Donne constructs a five-stanza argument to show his love's utmost strength and purity. Each stanza starts and finishes with the word "love." The poem is unified around a common topic by the words that finish each stanza's fourth and eighth lines with a -ove (the pattern is continuously abbacccaa). The opening few words of the poem seem more like a line spoken on stage than the saints and religious practices implied by the title. The phrase "for God's sake, hold your tongue" is so offensive when it comes after the revered title. By the poem's conclusion, the reader has concluded that "canonization" refers to the process by which the poet's love would be accepted as an example of pure love and used by others to evaluate their own romantic relationships. We shall see that Donne puts forth the perfection of divine love as the sole realistic model for all others since, as usual, this exaggeration also invites the reader to discover a spiritual or philosophical interpretation in the poem. The poet laments that his verbal attacker is mistaken in the opening verse. Has he nothing more important to do than disparage the affection of others? He may easily target Donne's "gout" or "palsy" (line 2) or even his "five grey hairs" (line 3), but he ought to find employment, enroll in school, or start a career as long as he leaves the poet alone. Most likely, the king's "stamped face" (line 7) alludes to coins bearing his portrait. As long as the critic "will let me love (line 9)," I can leave the world's goods to the critic and the world. "Who's injured by my love?" asks the second verse from a live-and-let-live individual rights standpoint (line 10). The couple isn't starting a war, defending against legal action, interfering with trade, or spreading illness. They do not intrude on other people's property; they respect it. As shown in the third paragraph, they each take risks on their own throughout their brief lives. The rest sees them of the world as little insects or as peaceful candles that will burn together. Although they may burn themselves to death in the process of being madly in love, Donne elevates their love to a higher level by the poem's midpoint. The Renaissance concept that the dove surpasses the heavens to reach heaven and the eagle soars in the sky above the ground is referenced in the first comparison he makes between himself and his loves and the eagle and dove. The poet then immediately switches to the image of the Phoenix. This bird repeatedly burns in the fire and emerges from the ashes, suggesting that even though their flames of passion will consume them, the poet and his beloved will be reborn from the ashes of their love. Their interaction has changed into a contradiction in their resurrection. Two people becoming one is the main contradiction of love. They "prove/Mysterious by this love" by joining together in this manner (lines 26-27). As mentioned by Paul in I Corinthians, these lines may allude to the mystery of marriage as it depicts the bond between Jesus and his followers. Although it includes both sexes, the new union is unexposed: "to one neutral thing both sexes fit," just as there is no longer a male or female in Christ (Galatians 3:28). Compare this to the romantic tale in Plato's Symposium, in which the primordial humans had traits of both sexes before being divided into male and female, leaving each to search for the other half. The fourth verse begins by pondering the poet's legacy of love for his lover. The vocabulary of "verse" and "chronicle" imply canonization at almost the level of Scripture, which is numbered by verses and contains volumes called Chronicles. Their love will live on in legend. Even if their love isn't nearly so intense, sonnets and songs will be written to celebrate their relationship. On the one hand, their love is flawless and self-contained, like a "well-wrought urn." (This expression gained notoriety when critic Cleanth Brooks authored a book considering each poem as its own exquisitely and painstakingly made urn, full unto itself, and poet John Keats penned "Ode on a Grecian Urn"). On the other hand, the ashes in this urn are designed to disperse; they already span half an acre, but this is symbolic of dispersing the story of ideal love across the globe. The poet's idea of coming justice against the critic is expressed in the last verse. In the same manner as Catholics "invoke" saints in their prayers, the poet anticipates that the rest of the world will do the same for him and his lover. In this futuristic scenario, the couple's reputation has flourished and attained a status akin to sainthood. Because "Countries, towns, courts beg from above/A pattern of your love" (lines 44-45), they serve as examples for the whole globe. The universe is present to the lovers as they gaze into one other's eyes; this establishes the model of love that the rest of the world may imitate.

Next TopicThe Crack-Up Summary

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share