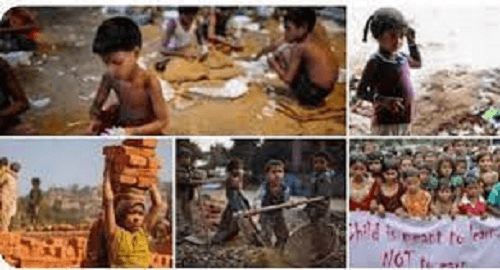

Child Labour EssayWhat is Child Labour?Child labour is a word that refers to the exploitation of children through any occupation that deprives them of their childhood, stops them from attending regular school, and is detrimental to their physical, mental, social, and moral development. The use of children for labour is forbidden by law everywhere. At the same time, some exceptions exist, such as work performed by young artists, household chores, supervised training, and various kinds of child labour used by Amish children and native children in the Americas.

Its ExistenceThroughout history, there have been varying degrees of child labour. Many young people from lower-class households aged 5 to 14 worked in Western countries and their colonies throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of these kids worked in agriculture, home-based manufacturing, factories, mines, and services like newsboys; some put in 12-hour nights at their jobs. The incidence rates of child labour decreased as household wealth increased, more schools became available, and child labour regulations were passed. Many children in the world's poorest nations work as minors, with sub-Saharan Africa having the highest rate (29%) of child labourers. More than 50% of children aged 5 to 14 who lived in Mali, Benin, Chad, and Guinea-Bissau in 2017 were employed. The most significant proportion of the child population in the world is seen to be engaged in child labour in agriculture. The World Bank reports that between 1960 and 2003, the prevalence of child labour declined from 25% to 10%. Despite this, many children are still working. As UNICEF and ILO reported, in 2013, 168 million children between the ages of 5 and 17 were employed in child labour globally. HistoryIn Preindustrial Societies

There was little room for normal childhood in the contemporary sense since children typically began actively participating in jobs like child-rearing, hunting, and farming as soon as possible. In many countries, children as young as 13 are considered adults and participate in the same activities as adults. Children's participation was critical in preindustrial cultures since children needed to offer labour for their existence and the survival of their society. Preindustrial cultures were characterised by poor productivity and short life expectancy; barring youngsters from partaking in productive activity would be more detrimental to their welfare and society in the long run. There was minimal need for children to attend school in a preindustrial community, especially in illiterate tribes. Most preindustrial skills and knowledge may be handed along through direct mentoring or apprenticeship by competent individuals. During Industrial Revolution

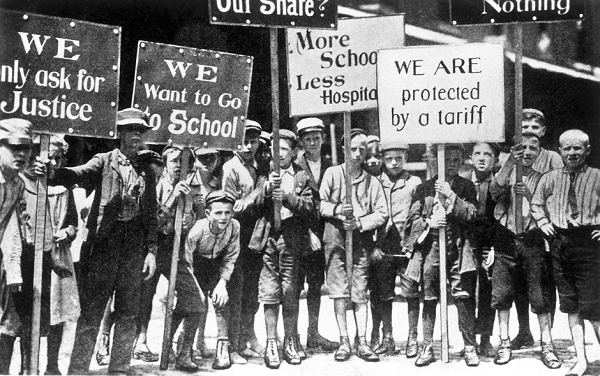

With the start of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century in the United Kingdom, there was a fast growth in the industrial exploitation of labour, including child labour. Industrial cities like Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool quickly evolved from tiny villages to huge metropoles, lowering child mortality rates. Because of increased agricultural productivity, these communities attracted a fast-rising population. The Victorian era, in particular, became famous for the working circumstances of youngsters. Children as young as four were deployed in industries and mines, working long hours in hazardous, often deadly, working conditions. In coal mines, kids would crawl through tunnels that were too narrow and low for adults. Children were also employed as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, or selling matches, flowers, and other low-cost items. Some youngsters worked as apprentices in respectable occupations like construction or household services. Child labour was vital throughout the Industrial Revolution, frequently caused by economic hardship. Poor children were expected to contribute to their family's income. One-third of Britain's low-income households in the nineteenth century were without a provider owing to death or desertion, forcing many children to labour from an early age. In 1788, two-thirds of the employees in 143 water-powered cotton mills in England and Scotland were classified as youngsters. A large percentage of children were also prostitutes. At 12, the novelist Charles Dickens worked with his family in a blacking workshop in a debtor's jail. Child wages were frequently as low as ten to twenty per cent of an adult male's salary. Karl Marx was a vocal critic of child labour, arguing that British firms "could only exist by sucking blood, and children's blood as well," and that "capitalised blood of children underlay American enterprise." Letitia Elizabeth Landon also criticised child labour in her 1835's poem The Factory; portions of this work were incorporated in her 18th Birthday Tribute to Princess Victoria, published in 1837. Due to regulations and economic circumstances brought about by the growth of trade unions, child labour began to drop in industrialised cultures in the second part of the nineteenth century. Since the commencement of the Industrial Revolution, child labour has been strictly regulated. The first law forbidding child labour in the United Kingdom was passed in 1803. Later, workhouse youngsters were only allowed to labour 12 hours a day in factories and cotton mills. These limitations were primarily ineffective, and in 1833 a royal commission recommended that children under the age of nine be prohibited from working and that minors between the ages of 11 and 18 be restricted to working no more than 12 hours each day. This was in response to radical agitation, such as the 1831 "Short Time Committees". This rule, however, only extended to the textile industry. In response to additional demonstrations, second legislation was issued in 1847 to limit the adults' and children's workforce hours to 10 hours/day. Lord Shaftesbury was a staunch proponent of child labour legislation. With the rise of technology, there was an increased demand for educated personnel. The final adoption of compulsory schooling increased educational achievement. Automation and improved technology have also resulted in the abolition of child labour. In 20th Century

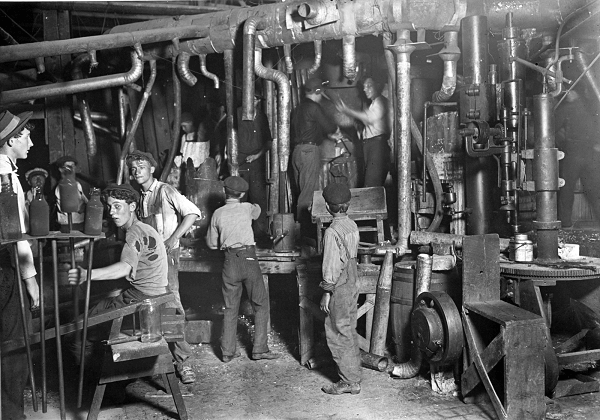

Numerous youngsters were engaged in the glass-making industry in the early 20th century. Making glass was a difficult and risky task, especially before modern technologies. About 3,133 °F (1,723 °C) of extreme heat is used to melt glass throughout the production process. The lads are exposed to tremendous heat while they are at work. Cuts, burns, heat fatigue, lung conditions, and eye and lung problems might result from this. The fact that the piece compensated the employees made them have to labour nonstop for long periods. Night shifts ran from 5:00 pm to 3:00 am because furnaces had to be blazing continuously. Many manufacturing owners chose boys under the age of 16. By 1900, 1.7 million children under fifteen were working in American industry. Over 2 million youngsters in the same age range worked in the U.S. in 1910. This included youngsters who worked in canneries, factories, bobbin doffer jobs in textile mills, coal mines, and the rolling of cigarettes. In Household Enterprises

Outside of mines and factories, child labour was widespread in the early 20th century in household enterprises. Children were engaged in home-based manufacturing throughout Europe and the United States. Governments and reformers claimed that factory labour needed to be controlled and that the state had a duty to support the underprivileged. The following regulations encouraged people to work from home rather than in factories. Because it allowed people to earn money while taking care of family responsibilities, families and women, in particular, enjoyed it. Manufacturing businesses operated out of their homes all year round. Families voluntarily employed their kids in these home businesses that generated revenue. Men frequently worked from home. Over 58 per cent of garment workers in France worked from their homes; between 1882 and 1907. Likewise, the number of full-time home businesses in Germany almost doubled. In the United States, millions of families worked seven days a week, 365 days a year, to produce clothing, shoes, artificial flowers, feathers, matchboxes, toys, umbrellas, and other goods. Alongside the parents, kids ages 5 to 14 also worked. Home-based businesses with child labour were widespread in Australia, Britain, Austria, and other nations. Families often sent their kids to work in agriculture in rural areas. The International Labour Organization was informed in 1946 by Frieda S. Miller, the U.S. Department of Labour director, that these home-based businesses provided "poor salaries, long hours, child labour, and unsanitary working conditions". In 21st Century

Child labour is still prevalent throughout most of the world. The amount of child labour is uncertain. If children aged 5 to 17 engaging in any economic activity are included, it may range between 250 and 304 million worldwide. ILO estimates there were 153 million child labourers aged 5 to 14 around the globe in 2008, excluding those who did occasional light work. This is around 20 million fewer than the ILO's estimated number of children working in 2004. About 60% of child labour was employed in agricultural pursuits, including farming, dairying, fishing, and forestry. Another 25% of child labourers worked service-related jobs, including retail, street vending, restaurants, loading and unloading merchandise, storing, picking and recycling garbage, polishing shoes, providing domestic assistance, and other jobs. The remaining 15% of workers were employed in home-based businesses, factories, mining, packing salt, running machinery, and similar jobs in the informal sector. Two out of every three employed children work alongside their parents in unpaid family work. Some kids serve as tour guides for visitors while also generating revenue for stores and eateries. About 70% of child labour is concentrated in rural regions and 26% in the unregulated urban sector. Contrary to common opinion, parents hire most child labourers rather than formal labour or worker. Typically, rural areas rather than metropolitan centres are where you will find children who labour for cash or in-kind benefits. Around the world, fewer than 3% of children aged 5 to 14 work away from their parents or in another family. In Asia, child labour makes up 22% of the workforce, compared to 32% in Africa, 17% in Latin America, and 1% in the US, Canada, and other wealthy countries. The percentage of children working varies substantially between nations and areas within those nations. With nearly 65 million, Africa has the most significant rate of child labourers between the ages of 5 and 17. Asia has the most children working as child labour, roughly 114 million, due to its enormous population. There are 14 million child labourers in Latin America and the Caribbean, despite having a lower total population density. Obtaining current statistics on child labour is challenging due to discrepancies across data sources over what counts as child labour. Government policy in some nations exacerbates this issue. For instance, the government's classification of child labour statistics as "very secret" makes it unclear how widespread child labour is in China. Although China has laws to discourage child labour, the practice persists, typically in the agricultural and low-skill service industries, small workshops, and industrial businesses. A list of products made using child labour or forced labour was published in 2014 by the U.S. Department of Labor. Twelve products were credited to China, and child labourers and indentured workers made most of them. The study included electronics, apparel, toys, and coal products. According to the Maplecroft Child Labour Index 2012 assessment, 76 nations provide grave concerns for global business operations. Myanmar, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, Burundi, Pakistan, and Ethiopia were the ten nations with the greatest danger in 2012, listed in decreasing order. For corporations looking to invest in the developing world and import goods from emerging markets, Maplecroft ranked the Philippines as the 25th riskiest of the major growth economies, followed by India on the 27th spot, China on the 36th spot, Vietnam on the 37th spot, Indonesia on the 46th spot, and Brazil on the 54th spot. CausesAccording to the International Labour Organization (ILO), child labour is mainly caused by poverty. A child's earnings are typically essential for their life or the home's survival in low-income households. Even if it is a small amount, the income from working children may make up between 25 and 40% of the home revenue. The same result has been reached by other academics, including Edmonds and Pavcnik on worldwide child labour and Harsch on African child labour. According to ILO, a significant contributing factor that pushes children into dangerous labour is a lack of viable alternatives, such as inexpensive schools and high-quality education. Children work because they are bored and have no other options. There are not enough adequate school facilities in many localities, especially rural ones, where child labour is rampant to 60 to 70 per cent. Even when schools are occasionally accessible, they are too far away, challenging to get to, expensive, or the quality of instruction is so subpar that parents question if attending school is worthwhile. Eliminating Child Labour

Purchasing goods assembled or otherwise made in developing nations using child labour has frequently been a concern. Others have expressed worry that if items made using child labour are avoided, these kids may be forced to choose riskier or more demanding careers, including prostitution or agriculture. For instance, a UNICEF study found that after the Child Labour Deterrence Act was passed in the United States, an estimated 50,000 children were fired from their jobs in the Bangladeshi garment industry, forcing many of them to turn to jobs like "stone-crushing, street hustling, and prostitution", which are "more dangerous than a garment production". Before the Industrial Revolution, almost all children worked in agriculture, claims Milton Friedman. Many of these kids switched from farm work to industrial jobs during the Industrial Revolution. Child labour decreased before and after legislation because parents could afford to send their kids to school rather than work as actual earnings increased over time. Child household work and involvement in the more significant (waged) labour market are qualitatively different, according to socialist and British historian E. P. Thompson, author of The Making of the English Working Class. Additionally, it has been questioned whether or not the experience of the industrial revolution is valuable in predicting current developments. Hugh Cunningham, an author of Children and Childhood in Western Society, has made the following observations: "In the 1950s, it was possible to assume that since child labour had decreased in the developed world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it would eventually do so in the rest of the world. Its inability to do so and resurgence in the industrialised world pose concerns about its place in any economy, be it national or international." Thomas DeGregori, a professor of economics at the University of Houston, wrote about this in an article for the Cato Institute, "it is clear that the technological and economic changes are crucial elements in getting kids out of the workforce and move into schools. They can then develop into responsible adults and enjoy longer, healthier lives. However, as they were in our ancestry until the late 19th century, working children are crucial for survival in many families in developing nations like Bangladesh. Therefore, while they fight to eradicate child labour, getting there entails trying several ways, and tragically there are also numerous political impediments." In 1992, the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) was founded to work toward these issues. The most extensive programme of its sort in the world, it ran in around 88 nations. IPEC collaborated with national and international organisations, NGOs, the media, children, and their families to stop child labour and give children access to education and support. Through IPEC, the ILO ran the "Combating Abusive Child Labour (CACL-II)" initiative from 2008 to 2013. The key objectives of this program included helping children removed from the harshest types of child labour and generating alternative possibilities for vocational training and education. The project was mainly funded by the European Union, which contributed to the government of Pakistan. Oslo (1997), The Hague (2010), Brasilia (2013), Buenos Aires (2017), and most recently Durban (2022) have all been the places where global conferences were held. Many government officials, employees and workers of different organisations have periodically met to assess progress, identify remaining challenges, and agree on measures to end the worst forms of child labour by 2016. The Child Labour Global Estimates 2020's report was released in January 2021 by the ILO and UNICEF. According to the research, child labour declined by 38%, from 246 million in 2000 to 152 million in 2016. However, the number of youngsters working as minors grew by 9 million during COVID-19.

Next TopicNoise Pollution Essay

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share