C++ Static MemberMost of the time, you'll design classes so that any two instances of that class are independent. That is, if we have two objects, one and two, changes to one shouldn't affect two in any way. However, in some circumstances, we'll want to share data among all copies of a class. For example, we'll want all copies of a class to access a single global resource, or perhaps there's some initialization code we'd like to call when we create the first instance of a class. C++ thus provides the static keyword to create class-specific information shared by all copies of that class. Like const, static has nuances and, at times, can be counterintuitive. So, this handout discusses static member functions, their relation to const, and static data members. There are two ways to use static keywords in C++. They are:

Static Data MemberStatic data members are those declared using the "static" keyword. Whenever we declare a data member as static, either inside or outside a class called a static data member. There is only one copy of static data member even if many class objects exist. It is always initialized with zero because it is default value is zero. It is a shared memory for all class objects and retains its value. SyntaxIn other words, static data members are class-specific variables each class instance shares. If we have multiple class instances, each uses the same copy of that variable, so changes to static data members affect multiple objects. The syntax for declaring static data members is confusing since it exists in two steps - declaration and definition. For example, suppose you have the following class definition: From above, myStaticData has declared a static data member with the static keyword. However, the line static int myStaticData does not create the variable myStaticData. Instead, it simply tells the compiler that a variable called myStaticData must be declared at some point. Thus, to initialize myStaticData, we will need to add another line to our program that looks like this: int MyClass::myStaticData = 137; There are several important points to note here. First, when declaring the variable, we must use the fully-qualified name MyClass::myStaticData instead of just myStaticData. Second, we do not repeat the static keyword during the variable declaration - otherwise, the compiler will think we're doing something completely different. Finally, although myStaticData is declared private, we can still declare it outside the class definition. The reason for this two-part declaration/definition for static data is a bit technical. It concerns where the compiler allocates storage for variables, so for now, remember that static data has to be separately declared and defined. A data member in a class can be declared static. A static data member has certain special characteristics. These are:

Static data members look like regular data members in almost every aspect beyond declaration. Consider the following member function of MyClass called doSomething: Nothing here seems all that out-of-the-ordinary, and this code will work just fine. Note, however, that when we're modifying myStaticData, we are modifying a variable that any other instances of MyClass might be accessing. Thus it's important to make sure that we only use static data when we're sure the information isn't specific to any class. Static Member FunctionsIf we create a class member function as a static member function, it will access only static data members. It is also accessible if we do not have any object of a class. Member FunctionsDefining Member Function Member Functions can be defined in two places

A member function in a class can be declared static. A static member function has certain special characteristics, and these are:

Inside member functions, a special variable called this acts as a pointer to the current object. Whenever you're accessing instance variables, you're accessing the instance variables of this pointer. How does C++ know what value this refers to?The answer is subtle but important. Suppose we have a class MyClass with a member function doSomething that accepts two integer parameters. Whenever we invoke doSomething on a MyClass object using this syntax: myInstance.doSomething(a, b); Member function inside the class

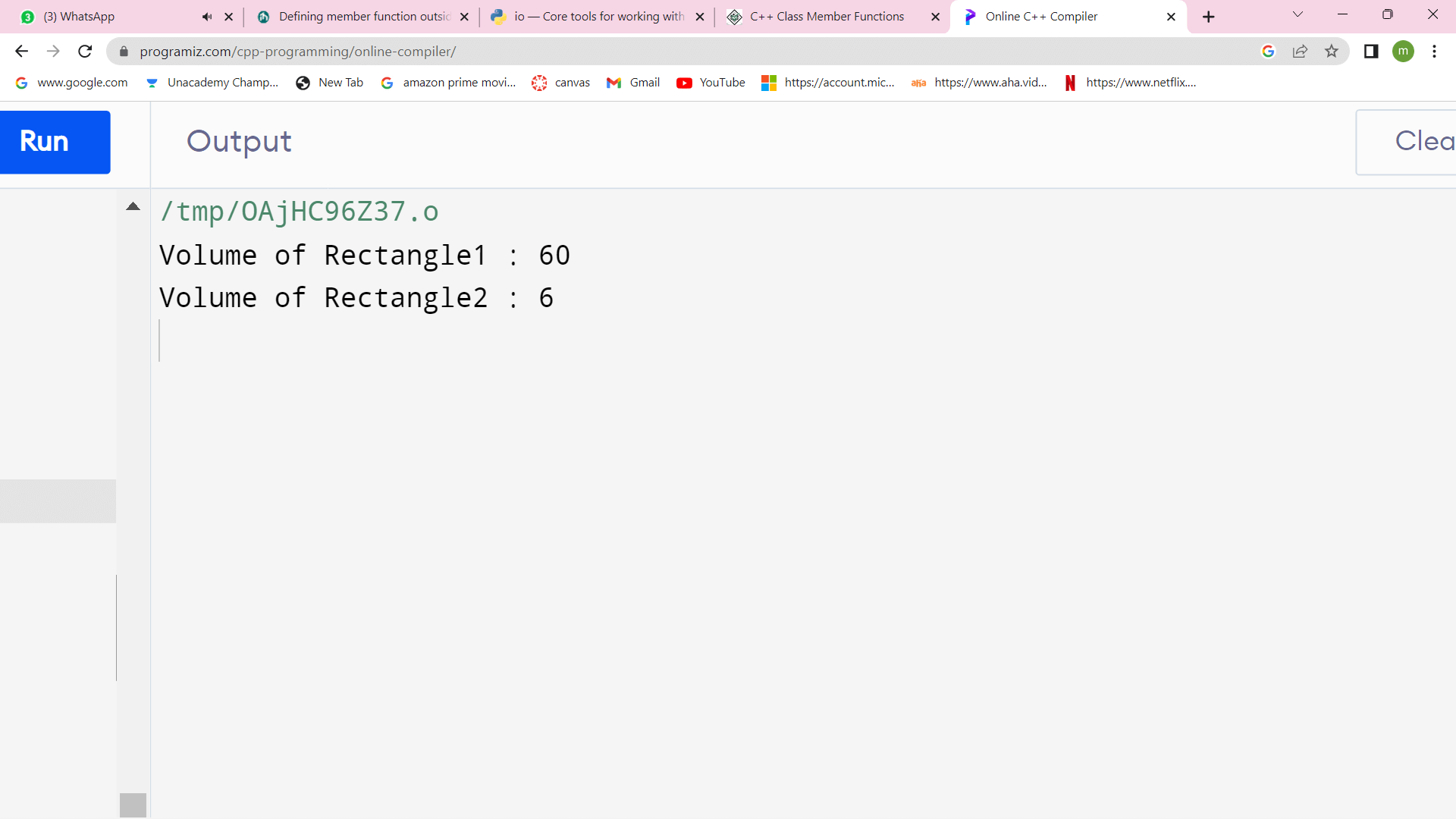

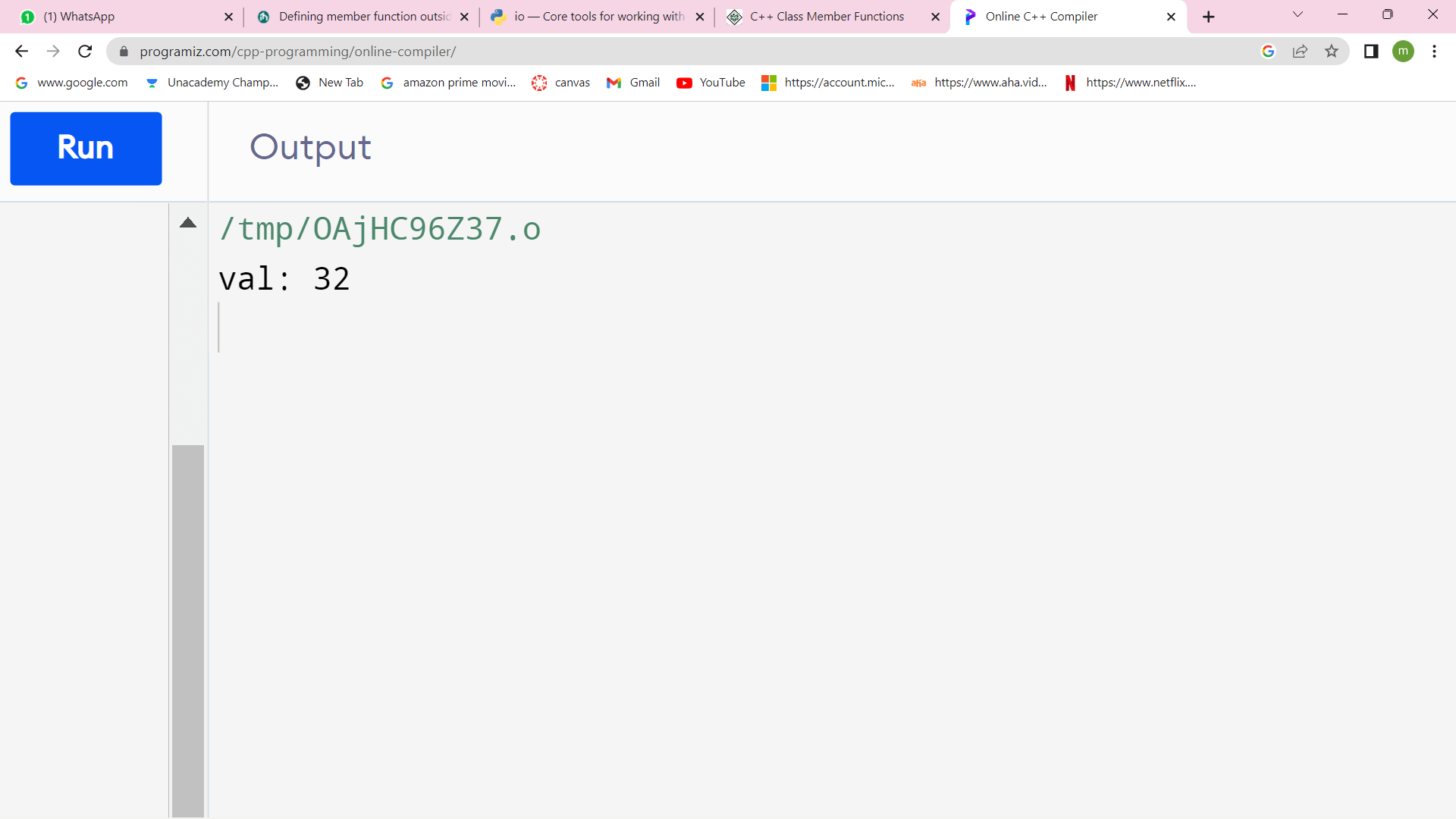

Code for the member function declarationOutput:

Explanation In the above program, the member functions getdata() and display() are defined inside the class in the public section. In main(), object one is declared. We know that an object can access the class's public members. Object one invokes the public member function getdata() and initializes their values, and display() invokes to display the result as an output. You're calling: doSomething(&myInstance, a, b); Where doSomething is prototyped as void doSomething(MyClass *const this, int a, int b) For almost all intents and purposes, this is a subtle distinction that, from your standpoint as a programmer, should be of little interest. However, the fact that an N-argument member function is an N+1-argument-free function can cause problems in a few places. For example, suppose you're writing a class Point that looks like this: If we have a vector that we'd like to pass to the STL sort algorithm, we'll run into trouble if we try to use this syntax: sort(myVector.begin(), myVector.end(), &Point::compareTwoPoints); The problem is that the sort function expects a function that takes two parameters and returns a bool. However, we've provided a function with three parameters: two points to compare and an invisible "this" pointer. Thus the above code will generate an error. Member function outside the class Member function outside the class is defined when the function is large. The following steps should be followed to define a function outside the class.

Syntax The following example illustrates the function defined outside the class. Output:

Characteristics of Member Function

Next TopicC++ Static Variable

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share