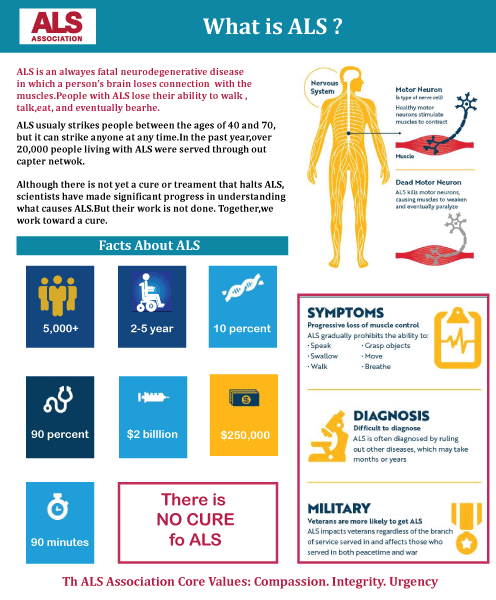

Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisThe uncommon neurodegenerative illness Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Motor Neurone illness (MND) or Lou Gehrig's Disease, causes the gradual loss of motor neurons that regulate voluntary muscles. The most prevalent motor neuron disease is ALS. Muscular cramps, stiffness, weakness gradually worsening, and muscular wastage are early signs of ALS. While bulbar-onset ALS starts with difficulties speaking or swallowing, limb-onset ALS manifests as weakness in the arms or legs. 15% of those with ALS acquire frontotemporal dementia, and nearly half of those with ALS have at least modest cognitive and behavioural impairments. The loss of motor neurons continues until the ability to move, talk, eat, and finally breathe is gone.

The majority of ALS cases (about 90% to 95%), sometimes referred to as sporadic ALS, have no recognised aetiology. However, it is thought that hereditary and environmental factors are at play. The remaining 5% to 10% of cases are classified as familial ALS (hereditary), which has a genetic basis and is often connected to a family history of the illness. One of four particular genes has disease-causing variations in almost half of these hereditary situations. A person's signs and symptoms are used to make the diagnosis, and testing is done to rule out any other probable reasons. diagnosis, and testing is done to rule out any other probable reasons. For ALS, there is no recognised treatment. Treatment aims to lessen symptoms and decrease the spread of the illness. Riluzole, which prolongs life by two to three months, and sodium phenylbutyrate/ursodoxicoltaurine, which prolongs life by around seven months, are two treatments that delay the progression of ALS. Non-invasive ventilation may increase life span and enhance quality of life. Although it may increase survival, mechanical ventilation does not halt the spread of illness. A feeding tube could assist in preserving nourishment and weight. In most cases, respiratory failure results in death. Although it may afflict anybody at any age, the illness often manifests itself around the age of 60. Two to four years is the typical survival time from the time of beginning to death. However, this may vary, and 10% of individuals who are afflicted continue to live for more than ten years. The sickness was first desrcibed at least in 1824 by Charles Bell. French doctor Jean-Martin Charcot identified the link between the symptoms and the underlying neurological issues in 1869; he first used amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 1874. HistoryThe sickness was first desrcibed at least in 1824 by Charles Bell. Fran�ois-Amilcar Aran was the first to identify a variant of ALS in which only the lower motor neurons are harmed, and he called it "progressive muscular atrophy" in 1850. Jean-Martin Charcot originally identified the link between the symptoms and the underlying neurological issues in 1869; he subsequently coined the name "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis" in his 1874 study. Alfred Vulpian was the first to identify the flail arm syndrome, a localised form of ALS, in 1886. In 1918, Pierre Marie and his pupil Patrikios published the first desrciption of flail leg syndrome, another localised form of ALS. Signs and SymptomsDue to the degeneration of the upper motor and lower motor neurons, the condition results in muscular weakness, atrophy, and spasms throughout the body. The majority of persons with ALS still have their senses of hearing, sight, touch, smell, and taste because sensory nerves and the autonomic nervous system are often untouched. Initial symptomsThe early signs of ALS may be so subtle that they go unnoticed. Muscle atrophy or weakness, usually on one side of the body, are the first signs of ALS. Other signs and symptoms may include difficulty breathing or swallowing, muscular cramps or stiffness, arm or leg paralysis, or slurred and nasal speech. Depending on which motor neurons in the body are initially injured, different body regions are affected by the early ALS symptoms. The arms or legs often exhibit the earliest signs of ALS in limb-onset cases. When walking or jogging, individuals may stumble or feel uncomfortable if their legs are affected first; this is sometimes indicated by walking with a "dropped foot" that drags lightly on the ground. If the arms are initially affected, the person may have trouble with manual dexterity-required activities like buttoning a shirt, writing, or turning a key in a lock. The earliest signs of ALS with bulbar onset are difficulty swallowing or speaking. Speech may slur, take on a nasal quality, or become softer. There might be swallowing issues and a lack of tongue movement. A lower percentage of persons get "respiratory-onset" ALS, in which the breathing muscles in the intercostals are initially impaired. People gradually become more limited in their ability to move, swallow, talk, or form words (dysarthria). Spasticity and hyperreflexia, which are symptoms of upper motor neuron involvement, are characterised by tight, stiff muscles, including an excessive gag reflex. Although the illness does not directly cause pain, most ALS patients still feel discomfort as a symptom brought on by their decreased mobility. Muscular cramps, atrophy, and temporary muscular twitches that are visible beneath the skin (fasciculations) are all signs of lower motor neuron degeneration. ProgressionThe first afflicted body area is often the most impacted over time, and symptoms typically extend to an adjacent body region, even if the original location of symptoms and subsequent pace of disability development differ from person to person. As an example, symptoms that begin in one arm often progress to the next arm or the leg on the same side. Patients with arm-onset symptoms often spread to the legs before the bulbar area, whereas patients with leg-onset symptoms typically spread to the arms rather than the bulbar region. Bulbar-onset individuals are more likely to have their next symptoms in their arms than their legs. Regardless of where symptoms first appeared, most patients ultimately lose the ability to walk or use their hands and arms freely. They could become less consistently unable to talk and swallow meals. The final cause of life-shortening in ALS is the gradual onset of respiratory muscle weakening, which results in the loss of the capacity to cough and breathe on one's own. The ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R), a 12-item instrument survey either as a clinician interview or self-reported questionnaire, may be used to calculate the rate of advancement. Its results range from 48 (normal function) to 0 (severe impairment). Doctors utilise the ALSFRS-R, which is the most often used outcome measure in clinical trials, to monitor the course of the illness. Even though there is a lot of variation and some ALS patients advance considerably more slowly than others, those who have the disease typically lose 1 ALSFRS-R point every month. Because the ALSFRS-R score is subjective, it may be influenced by medicine, and there are several ways to make up for changes in function; there may be brief stabilisation ("plateaus") or even slight reversals. The likelihood that these gains will be significant (more than 4 ALSFRS-R points) or long-lasting (lasting more than a year) is low (less than 1%). According to a poll of medical professionals, the most typical cutoff point for determining whether a new medication is effective in clinical trials is a 20% change in the slope of the ALSFRS-R. Disease Control at a Late StageDysphagia is the inability to chew or swallow properly, making eating challenging and increasing the danger of choking or aspirating food into the lungs. Aspiration pneumonia may occur in the latter stages of the condition, and it may become difficult to maintain a healthy weight, necessitating the placement of a feeding tube. Measures of lung function, including vital capacity and inspiratory pressure, decline when the rib cage's intercostal and diaphragm muscles that assist breathing deteriorate. This might happen in ALS with a respiratory start before there is obvious limb weakening. The disorder's most severe complication, locked-in syndrome, eventually causes sufferers to lose all voluntary motor control. Urinary and faecal incontinence are rare since bladder and bowel function are often unaffected, although having issues using the restroom might cause problems. The extraocular muscles that control eye movement are often unaffected, making it possible, if slow, to employ eye-tracking technology to enable augmentative communication. However, demands may alter with time. Despite these difficulties, a large number of patients with advanced illness report a decent level of health and quality of life. Survival, Staging, and PrognosisAlthough non-invasive ventilation used for respiratory support may lessen breathing issues and extend life, it does not impact how quickly ALS progresses. Most ALS patients pass within two to four years following their diagnosis. Approximately 50% of ALS patients pass away within 30 months of the onset of their symptoms, 20% live for five to ten years, and 10% live for ten years or more. The most frequent cause of mortality in ALS patients is respiratory failure, which is often hastened by pneumonia. After a time of deteriorating respiratory problems, a fall in their nutritional state, or a sharp worsening of symptoms, the majority of ALS patients pass away at home. Acute respiratory distress or sudden death are rare occurrences. Early access to palliative care is advised in order to address advance directives for healthcare, guarantee psychological support for the patient and carers, and explore choices. Similar to cancer staging, clinical trials for ALS employ one of four staging schemes with numbers ranging from 1 to 4. The King's staging system and Milano-Torino (MiToS) functional staging both originated around the same period. Although research is being done to develop statistical models based on prognostic criteria such as age at start, pace of advancement, location of onset, and existence of frontotemporal dementia, giving each patient a specific prognosis is presently not feasible. A population-based study found that patients with bulbar onset ALS had a median survival of 2.0 years and a 10-year survival rate of 3%, compared to patients with limb-onset ALS, who had a median survival of 2.6 years and a 10-year survival rate of 13%. Those with respiratory-onset ALS had a decreased median survival of 1.4 years and 0% survival at 10 years. Astrophysicist Stephen Hawking's case was remarkable since he continued to live for an additional 55 years after being diagnosed. Behavioural, Emotional, and Cognitive SymptomsIn 30 to 50% of people with ALS, there is cognitive impairment or behavioural dysfunction, and these symptoms might occur more often as the illness progresses. The most often reported cognitive symptoms in ALS are problems with verbal memory, executive dysfunction, social cognition, and language dysfunction. Patients with C9orf72 gene repeat expansions, bulbar onset, bulbar symptoms, family history of ALS, and a predominance of upper motor neuron phenotype are more likely to have cognitive impairment. About half of ALS patients exhibit emotional lability, a symptom in which patients weep, grin, yawn, or laugh?either in the absence of emotional cues or when they are experiencing the opposite emotion to that being expressed?and it is particularly prevalent in those with bulbar-onset ALS. Despite being relatively innocuous in comparison to other symptoms, it may promote social isolation and stigma since others around the patient find it difficult to respond to frequent and inappropriate outbursts in public. Around 10-15% of people also have modest cognitive deficits that may only become apparent during neuropsychological testing, which are additional symptoms of frontotemporal dementia (FTD). The most often reported behavioural symptoms of ALS are repetition of words or gestures, indifference, and lack of inhibition. Due to their genetic, clinical, and pathological similarities, ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are currently regarded as two distinct but related diseases (ALS-FTD). About 40% of genetic ALS and 25% of genetic FTD are caused by repeat expansions in the C9orf72 gene. A poorer prognosis is linked to cognitive and behavioural problems because they may lead to less adherence to medical advice and weaknesses in empathy and social cognition, which may lead to a heavier carer load. Causes of Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisBecause the aetiology of sporadic ALS is unknown, the condition is referred to as being idiopathic. Genetic and environmental variables are assumed to play nearly equal roles in its development despite the actual aetiology being unclear. Environmental variables are less well-known than genetic ones; no one environmental factor has been shown to be the direct cause of ALS. Cellular damage is thought to accrue over time as a result of genetic characteristics present at birth and exposure to environmental dangers throughout life, according to a multi-step liability threshold model for ALS. Although ALS may begin at any age, its probability rises with advancing years. At the time of diagnosis, patients with ALS are typically between the ages of 40 and 70, with an average age of 55. Men are 20% more likely than women to get ALS, although this gender disparity disappears in those whose disease manifests beyond age 70 1. Genetic Testing and GeneticsALS may be categorised as either familial or sporadic. However, they seem similar clinically and pathologically, depending on whether there is a known family history of the condition and if an ALS-associated genetic mutation has been discovered by genetic testing. It is estimated that monogenic, oligogenic, and polygenic modes of inheritance may all be present in familial ALS cases, which make up about 10-15% of all cases. Only about half of practitioners raise the potential of genetic inheritance with their patients, especially if there is no obvious family history of the illness. Clinical approaches to genetic testing in ALS vary widely. Previously, individuals with clearly familial ALS were the only ones eligible for genetic counselling and testing. However, it is becoming more widely acknowledged that instances of sporadic ALS may also be brought on by disease-causing de novo mutations in SOD1 or C9orf72, an incomplete family history, or incomplete penetrance, which means that a patient's grandparents had the gene but did not manifest the illness during their lives. Lack of historical records, smaller families, older generations dying earlier from causes other than ALS, genetic non-paternity, and uncertainty over whether certain neuropsychiatric conditions (such as frontotemporal dementia, other forms of dementia, suicide, psychosis, and schizophrenia) should be considered significant when determining a family history are some of the possible reasons for the absence of a positive family history. Since there is now a licenced gene treatment (terse) aimed solely at carriers of SOD-1 ALS, there have been requests in the scientific community to regularly advise and test all diagnosed ALS patients for familial ALS. This is difficult in practice due to a lack of genetic counsellors, a lack of clinical capacity to visit such at-risk patients, and uneven access to genetic testing globally. More than 40 genes have been associated with ALS, of which four account for nearly half of familial cases and around 5% of sporadic cases: C9orf72 (40% of familial cases, 7% sporadic), SOD1 (12% of familial cases, 1-2% sporadic), FUS (4% of familial cases, 1% sporadic), and TARDBP (4% of familial cases, 1% sporadic), with the remaining genes mostly accounting for fewer than 1% of either familial or sporadic cases. Approximately 15% of sporadic ALS cases and approximately 70% of familial ALS are now understood to have ALS genes. In general, there is a 1% chance that first-degree relatives of someone with ALS will also get the disease. 2. Environmental Concerns and Other FactorsAccording to the multi-step theory, a person's lifelong accumulation of environmental exposures, or exposome, and their genetic risk factors for the illness combine in some way to create the disease. Other than genetic abnormalities, the most often reported lifetime exposures to ALS include heavy metals like lead and mercury, organic compounds like pesticides and solvents, electric shock, physical trauma including head injuries, and smoking (more frequently in males than women). These effects are minimal overall, with each exposure slightly raising the risk of an uncommon disorder. For instance, if a person is exposed to heavy metals, their lifetime chance of acquiring ALS may go from "1 in 400" to between "1 in 300" and "1 in 200" without the exposure. Weaker evidence supports a number of other exposures, such as playing professional sports, having a lower BMI, less schooling, physical labour, military service, exposure to beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), and viral infections. Although openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness seem extremely prevalent among ALS patients, it is still unclear if personality might directly enhance their vulnerability to ALS. Instead, personality features that are inherited from parents may also predispose persons to ALS, or the personality, as mentioned above traits, may influence lifestyle decisions that may increase the risk of ALS. DiagnosisA single test cannot make a definitive diagnosis of ALS. Instead, a doctor must rely heavily on the patient's symptoms and signs to make the diagnosis of ALS, along with a battery of tests to rule out other conditions. To determine if symptoms like muscular weakness, atrophy of the muscles, hyperreflexia, Babinski's sign, and spasticity are worsening, doctors generally gather a patient's complete medical history and do a neurologic examination on them regularly. There are many biomarkers being researched for the illness. However, they won't be widely used until 2023. Different Diagnosis Appropriate tests must be carried out to rule out the potential of other problems since the symptoms of ALS may be similar to those of a broad range of other, more curable diseases or disorders. Electromyography (EMG), a unique recording method that finds electrical activity in muscles, is one of these examinations. A specific EMG result may help confirm the ALS diagnosis. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) is measured using another frequent test. Specific anomalies in the NCV findings may indicate that the patient does not really have ALS but rather a kind of peripheral neuropathy (injury to peripheral nerves) or myopathy (muscle illness). A spinal cord tumour, multiple sclerosis, a herniated disc in the neck, syringomyelia, or cervical spondylosis may all be shown on an MRI despite the fact that it is often normal in persons with early-stage ALS. The doctor may request normal laboratory testing, blood and urine tests to rule out the potential of other illnesses, and other tests based on the patient's symptoms, the results of the examination and these tests, among other things. A muscle biopsy may be carried out in specific circumstances, such as when a doctor feels a person may have a myopathy rather than ALS. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV), Lyme disease, and syphilis are among the infectious disorders that may sometimes manifest symptoms similar to those of ALS. Considerable consideration should be given to neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis, post-polio syndrome, multifocal motor neuropathy, CIDP, spinal muscular atrophy, and spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy since they may also mirror certain symptoms of the illness. The term "ALS mimic syndromes" refers to a group of unrelated conditions that might develop and exhibit clinical characteristics that are similar to those of ALS or its variations but must be distinguished from ALS. Neurologists may conduct examinations to assess and rule out other diagnosis options since the prognosis of ALS and closely similar subtypes of motor neuron disease is often poor. ALS may also resemble neuromuscular junction disorders, such as myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, albeit this seldom causes diagnostic challenges over time. Sometimes, the early signs of ALS may also be confused with benign fasciculation syndrome and cramp fasciculation syndrome. Even so, the lack of further neurological symptoms that inescapably accompany ALS implies that, over time, the difference will not pose any challenges to the skilled neurologist; in cases where there is still some uncertainty, an EMG may be beneficial. Management of the DiseaseALS has no known treatment. To enhance quality of life and extend survival, management focuses on treating symptoms and providing supportive care. The most effective way to provide this treatment is via multidisciplinary teams of medical experts; taking part in a multidisciplinary ALS clinic is linked to longer survival, fewer hospital stays, and better quality of life. The primary method of therapy for respiratory failure in ALS is non-invasive ventilation (NIV). It improves quality of life and extends longevity by around seven months in those with normal bulbar function. According to one research, NIV is useless for persons with impaired bulbar function, while another concluded that it could have a small survival advantage. Many ALS patients have trouble with NIV. When NIV is insufficient to control a person's symptoms of advanced ALS, invasive ventilation is an alternative. Invasive ventilation increases survival time, but illness development and functional deterioration persist. It might worsen ALS patients' or their carers' quality of life. In comparison to North America or Europe, Japan uses invasive ventilation more often. Through stretching, range-of-motion, and cardiovascular activities, physical therapy may help patients achieve functional independence. Through adaptable equipment, occupational therapy may help with daily life tasks. Speech therapy may help ALS patients who have trouble speaking. In ALS patients, preventing weight loss and malnutrition increases survival and quality of life. Dysphagia may first be treated with food modifications and swallowing skills. If a person with ALS loses 5% or more of their body weight or cannot properly swallow meals and liquids, a feeding tube should be considered. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is typically used to place the feeding tube. PEG tubes may increase survival, albeit the data is not strong. The goal of PEG implantation is often to enhance quality of life. Palliative treatment should start as soon as an ALS diagnosis is made. People with ALS have more time to consider their preferences for end-of-life care when discussing end-of-life concerns, which can help them avoid undesired interventions or procedures. The likelihood of a peaceful death is increased, and symptom management at the end of life can be improved by hospice care. Opioids can be used to alleviate pain and dyspnea in the later stages of life, while benzodiazepines can be used to manage anxiety. MedicationsTreatments that Slow Disease It has been discovered that riluzole modestly extends survival by two to three months. Those with bulbar-onset ALS may benefit more from it in terms of survival. It might function by reducing pre-synaptic neurons' ability to release the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate. The most typical adverse effects include asthenia (a lack of energy) and nausea. Riluzole treatment for ALS patients should start as soon as possible after diagnosis. Riluzole comes in pill, liquid, and dissolvable oral film forms. In a limited number of patients with early-stage ALS, edaravone has been proven to reduce the loss of function slightly. It might function by preventing oxidative stress on motor neurons. Bruising and gait disruption are the most frequent adverse effects. Both an oral solution and an intravenous infusion of edaravon are available. Combining taurursodiol with sodium phenylbutyrate, AMX0035 (Relyvrio) has been demonstrated to extend patient survival by an average of six months. Relyvrio is a powder that can be given orally or through a feeding tube after being dissolved in water. In April 2023, Tofersen (Qalsody), an antisense oligonucleotide, received medical approval in the United States for the treatment of SOD1-related ALS. There was a non-significant trend towards slowing progression in a trial of 108 patients with SOD1-associated ALS, as well as a substantial decline in neurofilament light chain, a putative ALS biomarker assumed to reflect neuronal damage. An open-label extension and follow-up research revealed that earlier therapy commencement slowed the course of the disease. Tofersen can be administered intrathecally into the lumbar cistern, which is located at the base of the spine. Symptomatic Treatments Additional drugs may be taken to help with weariness, ease muscle cramps, regulate spasticity, and reduce excessive saliva and phlegm. While nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and opioids can be used to treat nociceptive pain, gabapentin, pregabalin, and tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline) can be used to treat neuropathic pain. Tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective treatments for depression, whereas benzodiazepines are effective for treating anxiety. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) cannot be treated with medicine; however, some FTD symptoms can be managed with SSRIs and antipsychotics. The most widely used oral medications for treating spasticity are baclofen and tizanidine; an intrathecal baclofen pump can be used for severe spasticity. When ALS patients start experiencing difficulty swallowing their saliva (sialorrhea), doctors may administer atropine, scopolamine, amitriptyline, or glycopyrrolate. Based on a 2016 randomised controlled study, a 2017 review found that mexiletine is safe and effective for relieving ALS cramping. Support for BreathingNon-Invasive ventilation The main treatment for respiratory failure in ALS patients is non-invasive ventilation (NIV), which was the first therapy to demonstrate improvements in quality of life and survival. NIV supports breathing by using a face- or nasal mask attached to a ventilator that delivers sporadic positive pressure. People with ALS shouldn't apply continuous positive pressure since it makes breathing more challenging. NIV is initially only used at night since decreased gas exchange (hypoventilation) while sleeping is the earliest evidence of respiratory failure; symptoms linked to this nocturnal hypoventilation include disrupted sleep, anxiety, morning headaches, and daytime weariness. People with ALS eventually experience shortness of breath, whether at rest, during physical exercise or speech, and as the disease advances. Other symptoms include a weak cough, poor memory, confusion, respiratory tract infections, and poor concentration. The primary cause of death in ALS is respiratory failure. ALS patients should have their respiratory function checked every three months since starting NIV immediately after the onset of respiratory symptoms, which is linked to a higher survival rate. This entails assessing the respiratory function and determining if the ALS patient has any respiratory symptoms. Although upright forced vital capacity (FVC) is the most often used assessment, it is a poor indicator of early respiratory failure. It is not a viable option for those with bulbar symptoms because they have trouble keeping a tight seal around the mouthpiece. A more accurate way to assess diaphragm weakening is to test FVC when the subject is lying on their back (supine FVC). A quick and practical way to measure the diaphragm's strength is the SNIP test, unaffected by weak bulbar muscles. A midday blood gas study should be performed on an ALS patient with respiratory failure symptoms and signs to check for hypoxemia (low blood oxygen levels) and hypercapnia (excessive carbon dioxide levels in the blood). If their blood gas analysis performed during the day is normal, they should undergo nocturnal pulse oximetry to check for hypoxemia while they sleep. Survival is prolonged more by non-invasive ventilation than by riluzole. NIV improves quality of life and extends longevity by roughly 48 days, according to a 2006 randomised controlled experiment; however, it was also shown that some ALS patients benefit from this intervention more than others. NIV dramatically improves quality of life and extends longevity by roughly seven months in patients with normal or mildly compromised bulbar function. NIV does not increase life expectancy or quality of life for those with impaired bulbar function, although it does alleviate certain sleep-related symptoms. Despite the obvious advantages of NIV, roughly 25-30% of all ALS patients find it intolerable, particularly those with cognitive impairment or bulbar dysfunction. NIV should be made available to all ALS patients, even though it is expected that they may find it difficult to tolerate, according to findings from a large cohort research published in 2015. The results showed that NIV may increase survival in individuals with bulbar weakness. Invasive ventilation Through a tracheostomy (cut in the trachea), invasive ventilation bypasses the nose and mouth (the upper airways) and instead inserts a tube that is linked to a ventilator into the trachea. It is an alternative for those with severe ALS whose respiratory symptoms are not well controlled despite ongoing NIV usage. Invasive ventilation increases life expectancy, particularly in those under 60, but it does not stop the underlying neurodegenerative process. The person with ALS will continue to lose their ability to move, which will make communication more difficult and sometimes result in locked-in syndrome, which leaves them fully paralysed save from their eye muscles. Most ALS patients who opt to have invasive ventilation indicate that their quality of life has decreased, although around half of them still think it is adequate. Invasive ventilation, however, significantly affects carers and can reduce their quality of life. Different nations have different attitudes on invasive ventilation; in Japan, nearly 30% of ALS patients chose treatment, compared to fewer than 5% in North America and Europe. Therapy For those with ALS, rehabilitation often involves physical therapy. Particularly, physical, occupational, and speech therapists may create objectives and encourage benefits for ALS patients by minimising problems, postponing weakness loss, preserving endurance, reducing discomfort, enhancing speech and swallowing, and fostering functional independence. Through the course of ALS, occupational therapy and specialised tools like assistive technology may also increase people's independence and safety. Activities of daily living, such as walking, swimming, and stationary cycling, may assist patients in strengthening unaffected muscles, enhancing their cardiovascular health, and combat weariness and depression. Exercises that increase the range of motion and flexibility may help stop painful muscular stiffness and shortening (contracture). Because overworking muscles may aggravate ALS symptoms rather than benefit those who have them, physical and occupational therapists can suggest workouts that provide these advantages without taxing the muscles. They may recommend equipment that keeps persons mobile, such as wheelchairs, braces, walkers, shower chairs and other bathroom accessories. Occupational therapists may provide or suggest equipment and adjustments so that persons with ALS can continue to be as safe and independent in their daily activities as feasible. Physical therapists can assist persons with ALS to breathe better by practising pulmonary physical therapy since respiratory insufficiency is the main cause of death. In order to strengthen the respiratory muscles and improve survival chances, this also involves manual aided cough treatment, lung volume recruitment training, and inspiratory muscle training. Working with a speech-language pathologist may be helpful for ALS patients who have trouble swallowing or speaking. These health experts may instruct clients in coping mechanisms, such as methods for making their voices louder and clearer. Speech-language pathologists can advise using low-tech communication tools like head-mounted laser pointers, alphabet boards, or yes/no signals as ALS progresses, as well as augmentative and alternative communication methods like voice amplifiers, speech-generating devices, or voice output communication devices. Nutrition In ALS patients, preventing weight loss and malnutrition increases survival and quality of life. Muscle atrophy increased resting energy consumption, and reduced food intake all contribute to weight loss in ALS. Approximately 85% of ALS patients have difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) at some time over the course of their illness, which causes malnutrition and weight loss. Regular evaluations of an ALS patient's weight and swallowing capacity are crucial. Initially, dietary adjustments and altered swallowing practices may be used to address dysphagia. First to appear is often trouble swallowing liquids, which may be controlled by switching to thicker drinks like fruit nectar or smoothies or by adding fluid thickeners to thin liquids like coffee and water. Foods that are soft, moist, and easy to swallow?rather than those that are dry, crumbly, or chewy?should be consumed by people with ALS. Additionally, they should be taught the right way to hold their heads when swallowing, as this might facilitate simpler swallowing. There is some preliminary evidence that high-calorie diets may prolong life and prevent future weight loss. If a person with ALS loses 5% or more of their body weight or cannot properly swallow meals and liquids, a feeding tube should be considered. This may take the form of a gastrostomy tube, which inserts a tube into the stomach through the wall of the abdomen, or (less often) a nasogastric tube, which inserts a tube into the stomach via the nose and the oesophagus. As a nasogastric tube is painful and may lead to oesophagal ulcers, a gastrostomy tube is better for long-term usage. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) operation is typically used to place the feeding tube. PEG tubes may increase survival, albeit the data is not strong. PEG insertion is often done to maintain medicine and nutrient intake in order to improve quality of life. Cutting down on what may otherwise be a lengthy amount of time spent eating at mealtimes compensates for decreased oral food intake, lowers the risk of weight loss and dehydration, and may reduce anxiety. End-of-life care Palliative care should start as soon as someone is diagnosed with ALS since it alleviates symptoms and improves quality of life without addressing the underlying illness. People with ALS have more time to consider their end-of-life care choices when concerns are discussed early. This may also assist in preventing unnecessary therapies or procedures. They may write up advance directives stating their feelings towards non-invasive ventilation, invasive ventilation, and feeding tubes after they have been properly educated about all elements of different life-prolonging methods. Dysarthria, which is difficulty speaking due to muscular weakness and cognitive impairment, may make it difficult for patients to express their desires for treatment later in the disease's course. Continued disregard for the ALS patient's wishes might result in unforeseen and undesirable emergency procedures, such as invasive ventilation. Use the introduction of gastrostomy or non-invasive ventilation to bring up end-of-life concerns if persons with ALS or their family members are hesitant to do so. Hospice care, also known as palliative care towards the end of life, is crucial for people with ALS because it improves symptom management and enhances the possibility of passing peacefully. The beginning of the end-of-life phase of ALS is not always evident, although it is characterised by severe difficulties in moving, speaking, and, in some instances, thinking. Although many ALS patients worry that they may suffocate or choke to death, they should rest confident knowing that this happens infrequently?less than 1% of the time. The majority of patients pass away at home, and in the last moments of their lives, benzodiazepines may be used to alleviate anxiety, and opioids can be used to relieve pain and dyspnea.

Next TopicBrain (Cerebral) Edema

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share