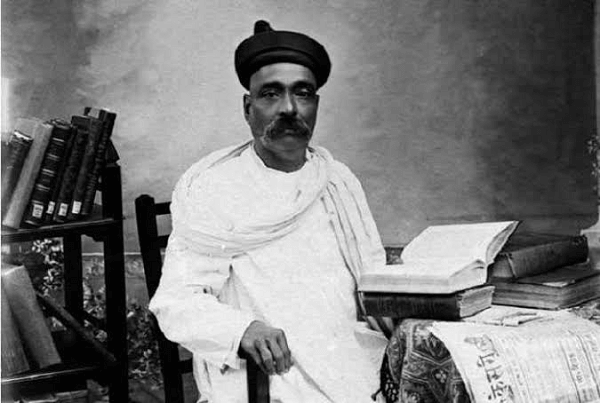

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Keshav Gangadhar Tilak, often referred to as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, was a journalist, schoolteacher, and campaigner for Indian freedom. The Indian Independence Movement's initial leader was also Bal Gangadhar Tilak. He was among the three people that made up the Lal Bal Pal trio. The British colonial administration called him "The Father of Indian Unrest". The name "Lokmanya", which translates to "recognized as a leader by the people", was also given to him. Mahatma Gandhi referred to him as "The Creator of Modern India". Bal Gangadhar Tilak was a prominent extremist in Indian Society and one of Swaraj's earliest and most ardent followers. Early LifeOn 23rd July 1856, Keshav Gangadhar Tilak took birth in the administrative centre of the Ratnagiri district in the Indian state Maharashtra (called Bombay Presidency earlier) to a Marathi Hindu Chitpavan Brahmin family. His place of origin was Chikhali. When Keshav turned sixteen, his father, Gangadhar Tilak, passed away. He was a Sanskrit scholar and a teacher in school. Tilak married Tapibai (Née Bal) in 1871 when he was sixteen, a few weeks before his father passed away. She was given a new name Satyabhamabai after getting married. Tilak obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree in Mathematics from Deccan College, Pune, in 1877. In the middle of his M.A. studies, he switched to L.L.B. and left M.A. He graduated from Government Law College with his L.L.B. degree in 1879. Tilak began working as a math instructor in a private school in Pune after graduation. Later, he resigned and then became a journalist as a result of ideological conflicts with his classmates at the new institution. Tilak was involved in politics regularly. "Religion and practical life are not different", he said. Making the nation your family rather than working just for your own is a genuine attitude. Serving others is the next step, and serving God is the step beyond that. In 1880, he and a few of his college friends, including Vishnushastri Chiplunkar, Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, and Mahadev Ballal Namjoshi, co-founded the New English school for secondary education. Their goal was to improve the education of youth and create new opportunities in India. As a result of the school's success, they established the Deccan Education Society in 1884 to create a new educational framework that strongly emphasized Indian culture while instilling nationalist values in young Indians. The Fergusson College was founded by the Society in 1885 for post-secondary studies. Tilak was a mathematics instructor at Fergusson College. Tilak quit the Deccan Education Society in 1890 in favour of an activity that was more overtly political. He launched a widespread independence movement focused on a religious and cultural uprising. Political LifeTilak fought for Indian independence from British colonial control throughout his lengthy political career. He was the most well-known Indian prominent politician before Gandhi. In contrast to Gokhale, another Maharashtrian of the same generation, Tilak was a militant nationalist but a social conservative. He spent a significant amount of time behind bars, including at Mandalay. At one point in his career in politics, British novelist Sir Valentine Chirol referred to him as "The father of Indian Unrest". Journey through Indian National Congress

Tilak joined the I.N.C. in 1890. He disagreed with its moderate viewpoint, especially regarding the fight for self-government. He was one of the most well-known radicals of the time. The 1905-1907 Swadeshi movement caused the division between the Indian National Congress's moderates and extremists. From Bombay to Pune, the bubonic plague started to expand in the latter part of 1896, and so by January 1897, it had reached epidemic levels. Strict rules and regulations were put in place to prevent the plague, including the support of the British Indian Army. This mainly included home invasion into people's residences, investigation of the residents, evacuation to health facilities and isolation camps, removal and destruction of personal property, and barring patients from entering or leaving the city. The pandemic was under control by the end of May. In India, there was a lot of public resentment toward the pandemic-control efforts. Tilak took up this cause by writing provocative pieces for his newspaper Kesari (written in Marathi and "Maratha" in English), citing the Bhagavad Gita as authority to support his position that no one could be held accountable for killing an oppressor without considering receiving retribution. On June 22, 1897, the Chapekar siblings and their other accomplices shot and killed Commissioners Rand and Lt. Ayerst, a second British officer. Barbara and Thomas R. Metcalf claimed that Tilak "very certainly concealed the criminals' names". Tilak received an 18-month prison term after being accused of inciting murder. When he was released from prison in Mumbai, he was revered as a martyr and a national hero. His colleague Kaka Baptista's new tagline, "Swaraj (self-rule) is my birthright, and I shall have it", was adopted by him at that time. Tilak supported the Swadeshi campaign and the Boycott movement after the Bengal Partition, a plan devised by Lord Curzon to stifle the nationalist movement. The training included social rejection of any Indian who used foreign goods and did not boycott imported goods. Following the boycott of imported goods, manufacturing such items within India had to fill a gap. The Swadeshi movement promoted the consumption of things made in the country. According to Tilak, the Boycott and Swadeshi movements were mutually complementary. Tilak disagreed with Gopal Krishna Gokhale's moderate viewpoints and was backed by other Indian nationalists, including Bipin Chandra Pal in Bengal and Lala Lajpat Rai in Punjab. The phrase "Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate" was used to describe them. The conflict between the conservative and radical wings of the party erupted over the choice of the new Congress president. Tilak had the backing of political leaders like Aurobindo Ghose and V. O. Chidambaram Pillai. When asked in Calcutta if he imagined a Maratha-style of administration for independent India, Tilak replied that the Maratha-dominated governments of the 17th and 18th centuries were outmoded in the 20th century and that he wanted an actual federal state for Free India where everyone was an active participant. Only such a system of administration could protect India's freedom, he said. He was the first member of Congress to advocate for Hindi inscribed in the Devanagari script to be recognized as India's sole official language. Sedition ChargesTilak was tried three times by the British Indian Government for sedition during his lifetime, in 1897, 1909, and 1916, among other political trials. Tilak received an 18-month jail term in 1897 for advocating dissidence from the Raj. He was accused of sedition and escalating racial hostility between Indians and the British in 1909. While representing Tilak, Bombay attorney Muhammad Ali Jinnah was controversially found guilty and given a six-year prison term in Burma. When Tilak was accused of sedition for the third time in 1916 due to his self-rule lectures, Jinnah again represented him, and this time helped him win the case. Imprisonment in MandalayTwo Bengali teenagers named Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose accidentally killed two ladies riding in the carriage on April 30, 1908, while attempting to kill Chief Administration Magistrate Douglas Kingsford of repute from Calcutta. Bose was hung, while Chaki attempted suicide after being arrested. Tilak backed the revolutionaries and demanded quick Swaraj, or self-rule, in his publication Kesari. He was quickly accused of sedition by the government. After the hearing, a special jury found him guilty by a vote of 7:2. In addition to a $1,000 (US$13) fine, judge Dinshaw D. Davar sentenced him to six years in prison to be executed in Mandalay, Burma. Muhammad Ali Jinnah represented Tilak at the time. Press outlets harshly criticized Justice Davar's ruling as being inconsistent with the fairness of the British legal system. Previously, in 1897, when Tilak was accused of disloyalty for the first time, Justice Davar personally defended him. The court used some harsh criticisms in his sentencing against Tilak's behaviour. He disregarded the judicial restriction, and his statement to the jury revealed this to some extent. He denounced the publications, calling them "seething with sedition", advocating violence and endorsing murder. In Mandalay, from 1908 to 1914, Tilak was imprisoned. He studied and wrote while imprisoned, furthering his understanding of the Indian nationalist struggle. He authored the Gita Rahasya when he was incarcerated. Several copies of the book were sold, and the earnings were donated to support for Indian independence approach. Life after Mandalay

Tilak got diabetes while spending his time in the Mandalay jail. At the time of his release on June 16, 1914, this disease and the overall hardship of jail life had softened him. In August of that year, when World War I broke out, Tilak sent a telegraph to King-Emperor George V, pledging his support and using his speeches to drum up fresh soldiers for the cause. The Minto-Morley Reforms, also known as the Indian Councils Act, were approved by the British Parliament in May 1909. He praised it as "a notable advance in collaboration between the Rulers and the Ruled". He firmly believed that using violence slowed down political changes rather than accelerating them. He had given up on his desire for direct action in favour of agitations conducted "strictly via constitutional methods", a position that had long been supported by his competitor Gokhale, who was anxious for reconciliation with Congress. Tilak made an effort to persuade Mohandas Gandhi to abandon the concept of total nonviolence (also known as "Total Ahimsa") and pursue self-rule ("Swarajya") by all methods available. Gandhi valued Tilak's contributions to the nation and his conviction, even if he disagreed with him on how to obtain self-rule and remained staunch in his support of satyagraha. Gandhi also encouraged Indians to donate to the Tilak Purse Fund, which started paying Tilak's expenses after Tilak lost a legal case against Valentine Chirol and incurred financial loss. All India Home Rule LeagueBetween 1916 and 1918, Bal Gangadhar Tilak collaborated with G. S. Khaparde and Annie Besant to establish the All India Home Rule League. He attempted to reconcile the moderate and radical sections for years before giving up and concentrating on the Self Government League, which favoured self-rule. Tilak visited many villages in search of villagers' and farmers' support to join the self-rule movement. Tilak declared his adoration for Vladimir Lenin and was inspired by the Russian Revolution. In April 1916, there were 1400 members of the league, and by 1917, there were over 32,000. Maharashtra, the Central Provinces, Karnataka, and the Berar area were where Tilak established his Home Rule League. The remainder of India saw activity from the Besant's League. Thoughts and ViewsReligio-Political View

Throughout his life, Tilak worked to bring the Indian people together for widespread political activity. He argued that for this to happen, the anti-British, pro-Hindu movement needed to be fully defended. To do this, he looked for justification in the purported founding ideas of the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita. This incitement to activism was known as karma-yoga or the yoga of actions. According to his understanding, this idea was revealed in the Bhagavad Gita when Krishna urged Arjuna to kill his enemies (many of whom were his family members at the time) because it was his duty. Tilak believed that the Bhagavad Gita offered a powerful rationale for activity. But this ran counter to the dominant interpretation of the text at the time, which was influenced by renunciate ideas and the notion of deeds performed only for God. Ramanuja and Shri Guru Adi Shankaracharya, who represented the two dominant viewpoints at the time, reflected this. Tilak used Jnanadeva's interpretation of the Gita, Ramanuja's significant commentary, and his interpretation of the Gita to bolster his beliefs while writing his variations of the pertinent Gita passages. His top fight was against the renunciate ideologies of the day, which clashed with activity in the real world. He took considerable measures to reinterpret terms like karma, dharma, and yoga, as well as the idea of renunciation, to combat this. Since he centred his defence on Hindu religious symbols and lines, he alienated many non-Hindus, including the Muslims who began allying with the British for assistance. Social views against WomenBal Gangadhar Tilak was adamantly opposed to liberal ideas in Pune, such as social policies against untouchability and women's rights. Tilak used his publications, the Mahratta and Kesari, to aggressively oppose the founding of the first native girl's High school (now known as Huzurpaga) in Pune in 1885, including its curriculum. Tilak was likewise against intercaste weddings, especially those involving upper caste women and lower caste men. He urged the Deshasthas, Chitpawans, and Karhades, three Maharashtrian Brahmin tribes, to abandon "caste exclusivity" and engage in intermarried relationships. Despite his opposition to the age of consent bill, which raised the age of marriage for females from ten to twelve, Tilak was willing to sign a circular raising the age of marriage for girls to sixteen and boys to twenty. Rukhmabai, a child bride, was wed at age eleven but refused to move in with her husband. The spouse filed a claim to restore his marital rights; he initially lost the case but later appealed. Invoking interpretations of Hindu law, Justice Farran commanded Rukhmabai to "either live with her husband or undergo six months in prison" on March 4, 1887. Tilak supported this court's ruling and stated that it was followed by Hindu Dharmasutras. In response, Rukhmabai said she would instead go to jail than follow the verdict. Queen Victoria later annulled her marriage. After that, she subsequently completed her doctoral studies at the London School of Medicine for Women. Behramji Malabari, a Parsi social reformer, advocated the Age of Consent Act of 1891 to increase the age at which a girl was eligible for marriage. He mainly opposed the act after Phulamani Bai, an eleven-year-old who died in 1890 while engaging in sexual activity with her much old aged husband. However, Tilak opposed the Bill and said neither the English nor the Parsis had any authority over (Hindu) religious concerns. He said that the girl's "defective female parts" were to a fault and questioned how the husband could be "oppressed diabolically for undertaking an innocuous deed". He referred to the girl as one of nature's "dangerous freaks". When it came to human sexuality, Tilak was not progressive. He disapproved of Hindu women receiving a contemporary education. Instead, he had a more traditional perspective, considering women as domestic helpers who must put their demands behind their spouses and children. Two years before his death in 1918, Tilak declined to sign a resolution to end untouchability despite having spoken against it at a meeting. DeathTilak breathed his last on 1 August 1920 and died of cardiac arrest at the age of 64. He was suffering from malaria, which badly affected his lungs, and it also aided in cardiac arrest to some extent. Besides, he was not feeling well after being released from prison in Mandalay.

Next TopicLouis Armstrong

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share