T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot OM was a poet, essayist, publisher, dramatist, literary critic, and editor who lived from September 26, 1888, to January 4, 1965. He is a crucial poet in English-language Modernist poetry and is regarded as one of the twentieth century's essential poets. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri, to a famous Boston family, and travelled to England at the age of 25 to live, work, and marry. At the age of 39, he became a British citizen and renounced his American citizenship. Eliot initially gained national prominence in 1915 with his poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," which was deemed outrageous at the time of its publication. His other work includes "The Waste Land" (1922), "The Hollow Men" (1925), "Ash Wednesday" (1930), and Four Quartets followed (1943). He was also recognised for seven plays, the most notable of which were Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and The Cocktail Party (1937). (1949). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948 "for his exceptional, pioneering contribution to contemporary poetry." Life and EducationWilliam Greenleaf Eliot, Eliot's paternal grandfather, had gone to St. Louis, Missouri, to build a Unitarian Christian church. His father, Henry Ware Eliot (1843-1919), was a wealthy businessman who served as president and treasurer of the St Louis Hydraulic-Press Brick Company. His mother, Charlotte Champe Stearns (1843-1929), was a social worker, which was a new profession in the United States in the early twentieth century. Eliot was the last of six children to survive. He was named by maternal grandpa Thomas Stearns and was known as Tom to family and friends. Several things contributed to Eliot's childhood fascination with reading. As a kid, he had to overcome physical constraints. Due to a congenital double inguinal hernia, he was unable to participate in many physical activities and hence was unable to socialise with his friends. Because he was frequently alone, he acquired an interest in books. After learning to read, the little kid grew hooked with literature, preferring stories of savage life, the Wild West, or Mark Twain's thrill-seeking Tom Sawyer. Robert Sencourt, Eliot's friend, writes in his biography that the young Eliot "would often cuddle up on the window seat behind a big book, putting the narcotic of dreams against the anguish of existence." Second, Eliot attributed his literary vision to his hometown: "It is self-evident that St. Louis had a greater impact on me than any other setting. I believe there is something about having spent one's youth by the huge river that is incomprehensible to those who have not. I feel myself lucky to have been born in this city rather than Boston, New York, or London." From 1898 until 1905, Eliot attended Smith Academy, Washington University's boys' college preparatory division, where he studied Latin, Ancient Greek, French, and German. He began writing poetry at the age of 14 after being inspired by Edward Fitzgerald's translation of Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat. He described the results as bleak and depressing, and he destroyed them. "A Fable for Feasters," his first published poem, was written as a school assignment and appeared in the Smith Academy Record in February 1905. His oldest extant handwritten poem, an unnamed lyric, was also published there in April 1905, subsequently reworked and reissued as "Song" in The Harvard Advocate, Harvard University's student literary journal. In 1905, he also published three short stories: "Birds of Prey," "A Tale of a Whale," and "The Man Who Was King." The previous tale described his study of the Igorot Village while in St. Louis for the 1904 World's Fair. Thus, his interest in indigenous peoples preceded his study in anthropology at Harvard. Eliot spent his first 16 years of life in St. Louis, Missouri, at the house on Locust Street where he was born. He only returned to St. Louis for holidays and visits after leaving for college in 1905. Despite leaving the city, Eliot said to a friend, "Missouri and the Mississippi have made a greater effect on me than any other portion of the globe." Following his graduation from Smith Academy, Eliot spent a prior year at Milton Academy in Massachusetts, where he met Scofield Thayer, who subsequently authored The Waste Land. From 1906 to 1909, he attended Harvard College, gaining a Bachelor of Arts in an optional degree comparable to comparative literature in 1909 and a Master of Arts in English literature the following year. Because of his year at Milton Academy, Eliot was able to complete his Bachelor of Arts in three years rather than the normal four. According to Frank Kermode, the most pivotal event in Eliot's undergraduate career occurred in 1908, when he encountered Arthur Symons' Symbolist Movement in Literature. This brought him into contact with Jules Laforgue, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine. Eliot claimed that he would not have known about Tristan Corbière and his book Les amours jaunes if it hadn't been for Verlaine. Some of his poetries were published in the Harvard Advocate, and he became longtime friends with American writer and critic Conrad Aiken. After working as a philosophy assistant at Harvard from 1909 to 1910, Eliot travelled to Paris and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne from 1910 to 1911. He attended Henri Bergson seminars and read poems with Henri Alban-Fournier. Between 1911 and 1914, he returned to Harvard to study Indian philosophy and Sanskrit. Eliot met and fell in love with Emily Hale while attending Harvard Graduate School. In 1914, Eliot was offered a scholarship at Merton College, Oxford. He originally travelled to Marburg, Germany, for a summer programme, but when the First World War broke out, he moved to Oxford instead. At the time, Merton had so many American students that the Junior Common Room sponsored a motion declaring "that this society abhors the Americanization of Oxford." After Eliot reminded the students of how much they owed American culture, it was defeated by two votes. On New Year's Eve 1914, Eliot wrote to Conrad Aiken: "I despise university towns and university students, who are all the same, with pregnant spouses, spreading children, piles of books, and terrible pictures on the walls. Oxford is lovely, but I don't want to die." Eliot spent much of his time in London after leaving Oxford. For various reasons, this city had a profound and life-changing impact on Eliot, the most notable of which was his introduction to the prominent American literary character Ezra Pound. A link through Aiken resulted in a scheduled encounter, and Eliot visited Pound's flat on September 22, 1914. Eliot also paid a visit to Pound's apartment on September 22, 1914. The pound immediately judged Eliot "worth monitoring," and he is credited with supporting Eliot's budding career as a poet through social events and literary groups. According to historian John Worthen, Eliot "saw as little of Oxford as possible" during his time in England. Instead, he spent lengthy amounts of time in London with Ezra Pound and others, "some of the contemporary artists who have been spared by the war Pound was the most helpful, introducing him to everyone." Eliot, in the end, did not feel at home at Merton and departed after a year. He began teaching English at Birkbeck, University of London, in 1915. In 1916, he finished a PhD dissertation on "Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley" for Harvard, but he did not return for the viva voce test. Married Life

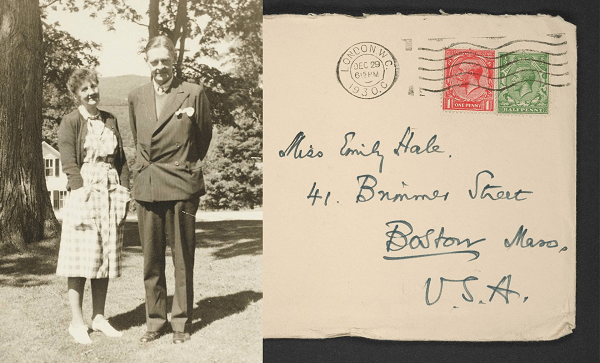

Before departing the United States, Eliot confessed his feelings for Emily Hale. He wrote to her from Oxford in 1914 and 1915, but they didn't meet again until 1927. "I am terribly reliant upon ladies (I mean female society)," Eliot, 26, said in a letter to Aiken late in December 1914. Thayer introduced Eliot to Vivienne Haigh-Wood, a Cambridge governess, less than four months later. On June 26, 1915, they married at Hampstead Register Office. After a brief solo visit to his family in the United States, Eliot returned to London and began lecturing at Birkbeck College, University of London. While the newlyweds were staying at Bertrand Russell's flat, the philosopher Bertrand Russell became interested in Vivienne. Some academics speculated that she and Russell had an affair, but the claims were never proven. The marriage was significantly unhappy, partly due to Vivienne's health issues. In a letter to Ezra Pound, she describes her symptoms, which include a persistently high fever, exhaustion, sleeplessness, headaches, and colitis. This, along with her apparent mental instability, meant that Eliot and her physicians frequently sent her away for prolonged periods of time in the aim of healing her health. And as time passed, he grew further estranged from her. The couple divorced in 1933, and Vivienne's brother, Maurice, had her sent to a mental hospital against her choice in 1938, where she died of heart illness in 1947. Their romance was the subject of the 1984 play Tom & Viv, which was made into a film of the same name in 1994. Eliot admitted in a private note in his sixties: "I convinced myself that I was in love with Vivienne merely because I wanted to destroy my ships and commit to living in England. And she convinced herself (again, influenced by Pound) that keeping the poet in England would rescue him. The marriage did not bring her happiness. It evoked the mental condition that gave rise to The Waste Land for me." Banking, Teaching and PublishingAfter leaving Merton, Eliot became a schoolteacher, most notably at London's Highgate School, where he taught French and Latin to students such as John Betjeman. He later taught at the Royal Grammar School in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire. He supplemented his income by writing book reviews and lecturing at evening extension courses at University College London and Oxford. In 1917, he began working on international accounts at Lloyds Bank in London. In August 1920, while visiting Paris with the artist Wyndham Lewis, he met the novelist James Joyce. Eliot described Joyce as arrogant, and Joyce questioned Eliot's talent as a poet at the time. Still, the two writers quickly became friends, with Eliot paying Joyce visits whenever he was in Paris. Wyndham and Eliot Lewis and Eliot maintained a strong connection, which led to Lewis's well-known portrait painting of Eliot in 1938. Eliot left Lloyds in 1925 to become a director at Faber and Gwyer (later Faber and Faber), where he stayed for the remainder of his career. He was in charge of publishing notable English poets such as W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Charles Madge, and Ted Hughes at Faber & Faber. British Citizenship and Conversion to AnglicanismEliot moved from Unitarianism to Anglicanism on June 29, 1927, and received British citizenship in November of the same year. He became a life member of the Society of King Charles the Martyr and a churchwarden at his parish church, St Stephen's, Gloucester Road, London. He declared himself an Anglo-Catholic, declaring himself a "classicist in literature, a royalist in politics, and an anglo-catholic [sic] in religion." After almost 30 years, Eliot commented on his religious beliefs, saying that he had "a Catholic cast of thought, a Calvinist ancestry, and a Puritanical disposition." He also had broader spiritual interests, stating, "I see the way of advancement for the contemporary man in his engagement with his self, with his inner being," and citing Goethe and Rudolf Steiner as examples. Peter Ackroyd, one of Eliot's biographers, stated that "[Eliot's conversion] served two functions. One: The Church of England gave Eliot hope, and I believe Eliot needed a place to rest. Second, it connected Eliot to the English community and culture." Divorce and RemarriageEliot had been considering divorce from his wife for some time by 1932. He took the Charles Eliot Norton position at Harvard for the 1932-1933 academic year, leaving Vivienne in England. He planned for a legal separation from her upon his return, avoiding all but one encounter with her between his departure for America in 1932 and her death in 1947. At 1938, Vivienne was admitted to the Northumberland House mental institution in Woodberry Down, Manor House, London, where she resided until her death. Despite the fact that Eliot was still legally her husband, he never visited her. Eliot had a strong emotional relationship with Emily Hale from 1933 through 1946. Eliot eventually destroyed Hale's letters to him, while Hale gave Eliot's to the Princeton University Library, where they will be kept sealed until 2020. When Eliot learned of the contribution, he created his own record of their relationship with Harvard University, which would be opened whenever the Princeton letters were opened. Eliot's partner from 1938 until 1957 was Mary Trevelyan of London University, who wished to marry him and left a comprehensive memoir. From 1946 until 1957, Eliot shared a flat in Chelsea with his friend John Davy Hayward, who gathered and handled Eliot's papers and dubbed himself "Keeper of the Eliot Archive." Hayward also compiled Eliot's pre-Prufrock poems, which were commercially released after Eliot's death under the title Poems Written in Early Youth. When Eliot and Hayward divorced in 1957, Hayward kept his collection of Eliot's papers, which he left to King's College, Cambridge, in 1965. Eliot married Esmé Valerie Fletcher, 30, on January 10, 1957, at the age of 68. In contrast to his previous marriage, Eliot was well acquainted with Fletcher, who had been his secretary at Faber & Faber since August 1949. They kept their wedding a secret; the ceremony took place at 6:15 a.m. in St. Barnabas' Church in Kensington, London, with just his wife's parents in attendance. Neither of Eliot's spouses bore him children. In the early 1960s, as his health deteriorated, Eliot worked as an editor for Wesleyan University Press, looking for new poets in Europe for publishing. Death and HonoursEliot died of emphysema on January 4, 1965, at his home in Kensington, London, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. His ashes were scattered in St Michael and All Angels' Church in East Coker, Somerset, the village from where his Eliot ancestors moved to America. A wall plaque in the church has a quote from his poem East Coker: "My beginning is also my end. My beginning is in my end." Eliot was honoured by the laying of a big stone on the floor of Poets' Corner in London's Westminster Abbey on the second anniversary of his death in 1967. The stone, designed by Reynolds Stone, has his birth and death dates, his Order of Merit, and a line from his poem Little Gidding: "the communication of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living." In 1986, a blue plaque was erected on the apartment building where he resided and died, No. 3 Kensington Court Gardens. His PoetryEliot wrote a tiny number of poems for a poet of his rank. He was aware of this from the beginning of his profession. He wrote to one of his former Harvard teachers, J.H. Woods, and said, "My reputation in London is based on a small collection of verse, which I maintain by publishing two or three additional poems each year. The only thing that counts is that they are flawless in their category so that each is an event." Typically, Eliot published his poems singly in newspapers, short booklets, or pamphlets before compiling them into collections. Prufrock and Other Observations was his debut collection (1917). More poems were published in Ara Vos Prec (London) and Poems: 1920 in 1920. (New York). These contained identical poems (although in a different order), with the exception that "Ode" in the British version was substituted with "Hysteria" in the American edition. In 1925, he combined The Waste Land with the poetry from Prufrock and Poems into one collection, Poems: 1909-1925, and included The Hollow Men. He later revised this work as Collected Poems. The exceptions are Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939), a collection of light verse; Poems Written in Early Youth, published posthumously in 1967 and consisting primarily of poems published in The Harvard Advocate between 1907 and 1910; and Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909-1917, published posthumously in 1997. In a 1959 interview, Eliot spoke on his country and its importance in his work: "My poetry has more in common with my great contemporaries in America than with anything published in my generation in England, in my opinion. That I am certain of. It wouldn't be the same, and I doubt it would be as good; to say it as gently as I can, it wouldn't be the same if I'd been born in England, and it wouldn't be the same if I'd stayed in America. It's a conglomeration of factors. But it has its origins, its emotional springs, in America." In her biography, Cleo McNelly Kearns writes that Indic traditions, particularly the Upanishads, heavily inspired Eliot. From the Sanskrit finale of The Waste Land through the "What Krishna meant" portion of Four Quartets, it is clear how profoundly Indic faiths, notably Hinduism, shaped his intellectual foundation. It should also be noted that, as Chinmoy Guha demonstrated in his book Where the Dreams Cross: T S Eliot and French Poetry (Macmillan, 2011), he was heavily affected by French writers ranging from Baudelaire to Paul Valéry. In his 1940 article on W.B. Yeats, he stated, "The type of poetry that I required to teach me the use of my voice did not exist in English at all; it was only found in French.

In 1915, Ezra Pound, the foreign editor of Poetry magazine, suggested to the journal's founder, Harriet Monroe, that she publish "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock." Although the figure Prufrock appears to be in his forties, Eliot composed the majority of the poem when he was just twenty-two. Its now-famous opening lines, which compare the evening sky to "a patient etherised upon a table," were deemed upsetting and unpleasant, particularly when Georgian Poetry was lauded for its derivations from nineteenth-century Romantic poets. Eliot's considerable study of Dante primarily influenced the poem's form, and it references various literary works, including Hamlet and the French Symbolists. An anonymous review in The Times Literary Supplement on 21 June 1917 provides insight into its reception in London. "The fact that these ideas came to Mr. Eliot's thoughts are doubtless of the utmost significance to anybody, including himself. They have nothing to do with poetry."

Eliot published "The Waste Land" in The Criterion in October 1922. The dedication to il miglior fabbro ('the greater craftsman') refers to Ezra Pound's considerable role in editing and moulding the poem from a long Eliot draught to the abbreviated version that appears in print. It was written during a terrible era in Eliot's life when his marriage collapsed, and he and Vivienne suffered from neurological problems. Eliot distanced himself from the poem's picture of despair before it was published as a book in December 1922. "As for The Waste Land, it is a thing of the past as far as I am concerned, and I am now leaning toward a new structure and style," he wrote to Richard Aldington on November 15, 1922. The poem is frequently viewed as a metaphor for the postwar generation's disenchantment. Eliot dismissed this viewpoint in 1931, writing, "When I published a poem called The Waste Land, some of the more sympathetic commentators said that I had articulated "a generation's disillusionment," which is nonsense. I may have conveyed for them their illusion of disillusionment, but that was not my purpose." The poem is noted for its ambiguity-its shifts between satire and prophecy, as well as its rapid changes of voice, location, and time. This structural intricacy is one of the reasons why the poem has become a touchstone of modern literature, a poetic analogue to James Joyce's Ulysses, which was released the same year. "April is the cruellest month," "I will show you fear in a handful of dust," and "Shantih shantih shantih"-the Sanskrit mantra that concludes the poem-are among its most well-known passages.

"The Hollow Men" was published in 1925. It was "the nadir of the epoch of despair and desolation given such brilliant expression in 'The Waste Land,'" according to critic Edmund Wilson. It is Eliot's most famous poem from the late 1920s. Its themes, like those of Eliot's earlier works, are overlapping and disjointed. The difficulties of hope and religious conversion, Eliot's broken marriage, and postwar Europe under the Treaty of Versailles (which Eliot detested). "The myths evaporate entirely in 'The Hollow Men,'" wrote Allen Tate of Eliot's style. This is a striking claim for a poem that is as indebted to Dante as anything else in Eliot's early work, to say nothing of modern English mythology-the "Old Guy Fawkes" of the Gunpowder Plot-or the colonial and agrarian mythos of Joseph Conrad and James George Frazer, which echo in The Waste Land, at least for textual reasons. His legendary method's signature "constant parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity" survived in excellent condition. The climax of "The Hollow Men" features some of Eliot's most famous lines: This is the way the world ends Not with a bang but a whimper.

"Ash Wednesday" is Eliot's first significant poem after his conversion to Anglicanism in 1927. It was published in 1930 and focused on the struggle that occurs when a person who has previously lacked faith gains it. It is sometimes referred to be Eliot's "conversion poetry," and it deals with the goal to progress from spiritual barrenness to hope for human salvation. Eliot's literary style in "Ash Wednesday" differed significantly from the poetry he had produced before his 1927 conversion, and his post-conversion style followed suit. His style grew less satirical, and the poems no longer included many characters speaking in conversation. Eliot's subject matter also shifted to his spiritual concerns and Christian beliefs. "Ash-Wednesday" received a lot of positive feedback from critics. Edwin Muir felt that it is one of Eliot's most touching poems, and maybe the "most perfect," even though everyone did not warmly accept it. Many of the more secular literati were put off by the poem's foundation in traditional Christianity.

Old Possum's Book of Practical CatsEliot released Old Possum's Collection of Practical Cats, a book of humorous poems, in 1939 ("Old Possum" was Eliot's affectionate nickname from Ezra Pound). The cover of the first edition featured artwork by the author. Alan Rawsthorne, a composer, adapted six of the poems for speaker and orchestra in his 1954 composition Practical Cats. Following Eliot's death, the book inspired Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical Cats, which premiered in London's West End in 1981 and opened on Broadway the following year. Four QuartetsEliot considered Four Quartets to be his best, and it was this work that earned him the Nobel Prize in Literature. It is made up of four long poems, each of which was initially published separately: "Burnt Norton" (1936), "East Coker" (1940), "The Dry Salvages" (1941), and "Little Gidding" (1942). Each is divided into four components. Although they transcend categorisation, each poem contains thoughts on the nature of time in some fundamental way-theological, historical, or physical-and its relationship to the human predicament. Each poem is related to one of the four classical elements: air, earth, water, and fire, in that order. The contemplative poem "Burnt Norton" opens with the narrator attempting to focus on the present moment while wandering through a garden, focusing on pictures and noises such as a bird, flowers, clouds, and an empty pool. The meditation takes the narrator to "the still point," where there is no endeavour to move someplace or feel location and time but instead experiences "a grace of sense." The narrator considers the arts ("words" and "music") about time in the last segment. The narrator is particularly interested in the poet's ability to manipulate "words (that)strain, Crack and occasionally break, under the stress (of time), under the tension, slip, slide, expire, decay with imprecision, (and) will not remain in place, Will not stay still." In contrast, the narrator says, "Love is itself immobile, Only the source and end of the movement, Timeless and undesired." "East Coker" continues the investigation of time and meaning, concentrating on the nature of language and poetry in a renowned passage. "I whispered to my spirit, remain still, and wait without hope," Eliot says, emerging from the darkness. "The Dry Salvages" explores the element of water through images of a river and the sea. It attempts to reconcile opposites: "The past and future are vanquished and reconciled." The Quartet "Little Gidding" (the element of fire) is the most widely performed. The poem is inspired by Eliot's experiences as an air raid warden during the Blitz, and he imagines meeting Dante during the German bombing. The beginning of the Quartets had become a violent everyday experience; this generates an animation in which he discusses love as the driving force behind all occasions for the first time. The Quartets conclude with Julian of Norwich's affirmation: "All shall be well, and All manner of thing shall be good." The Four Quartets draws on Dante's Christian theology, art, symbolism, and language, as well as the mystics St. John of the Cross and Julian of Norwich. His Known PlaysWith the notable exception of Four Quartets, Eliot devoted much of his post-Ash Wednesday creative energy to composing verse plays, generally comedies or dramas with redemptive endings. He had long been a critic and fan of Elizabethan and Jacobean verse plays, as seen by his references in The Waste Land to Webster, Thomas Middleton, William Shakespeare, and Thomas Kyd. "Every poet would like, I imagine, to be able to think that he had some direct societal usefulness..." he stated in a 1933 speech. He aspires to be a famous performer who can think for himself while wearing a sad or humorous mask. He wants to impart the delights of poetry not just to a bigger audience, but also to greater groups of people collectively, and the theatre is the finest venue for this." He remarked after The Waste Land (1922) that he was "now feeling toward a new shape and style." One idea he had in mind was to write a verse drama inspired by early jazz rhythms. The show included "Sweeney," a character from several of his writings. Despite the fact that Eliot did not complete the play, he did publish two scenes from it. These episodes, named Fragment of a Prologue (1926) and Fragment of an Agon (1927), were collected as Sweeney Agonistes in 1932. Even though Eliot said that this was not intended to be a one-act play, it is occasionally played as such. In 1934, Eliot's pageant drama The Rock was staged for the benefit of churches in the Diocese of London. Much of it was a joint effort, with Eliot taking credit solely for one scene and the choruses. The Bishop of Chichester, George Bell, was essential in linking Eliot with producer E. Martin Browne for The Rock's performance and later commissioned Eliot to write another play for the Canterbury Festival in 1935. Murder in the Cathedral, about the martyr Thomas Becket's death, was more within Eliot's control. According to Eliot's biographer Peter Ackroyd, "Murder in the Cathedral and later verse plays had a twofold advantage; it allowed him to develop poetry but also provided a natural home for his religious sensitivity." Following this, he worked on more "commercial" plays for a broader audience, including The Family Reunion (1939), The Cocktail Party (1949), The Confidential Clerk (1953), and The Elder Statesman (1958). (The latter three were produced by Henry Sherek and directed by E. Martin Browne). The Cocktail Party got the Tony Award for Best Play in 1950 for its Broadway staging in New York. While a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study, Eliot authored The Cocktail Party. Eliot characterised his playwriting approach: "When I set out to create a play, I begin with an act of choice. I choose an emotional scenario from which characters and a narrative will develop. Then lines of poetry may emerge, not as a result of the original impulse, but as a result of a subsequent stimulation of the unconscious mind." Literary CriticismEliot contributed substantially to literary criticism and impacted the New Criticism school of thought. He was rather self-deprecating and dismissive of his work, even claiming that his critique was only a "by-product" of his "secret poetry-workshop." However, critic William Empson once stated, "I am not sure how much of my thinking [Eliot] invented, let alone how much of it is a reaction to him or a result of misunderstanding him. He has a highly perceptive impact, similar to the east wind." In his critical essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent," Eliot argues that art must be appreciated in the context of past works of art rather than in isolation. "In a strange way, [an artist or poet] ... must unavoidably be assessed by prior standards." By proposing the concept that the worth of a work of art must be judged in the context of the artist's prior works, this article had a significant effect on New Criticism. This theme was used by Eliot in several of his works, particularly in his epic poem The Waste Land. The concept of an "objective correlative," as described in Eliot's essay "Hamlet and His Problems," which proposes a relationship between the words of the text and events, states of mind, and experiences, was also crucial to New Criticism. This idea acknowledges that a poem means what it says, but it also indicates that there might be a non-subjective assessment based on various-but potentially corollary-interpretations of a work by different readers. More extensively, New Critics were influenced by Eliot's classical ideals and religious thought; his attention to early seventeenth-century poetry and drama; his denigration of the Romantics, particularly Shelley; his proposition that good poems constitute 'not a turning loose of emotion but an escape from emotion. Eliot's articles had a significant role in rekindling interest in metaphysical poets. Eliot admired the metaphysical poets' capacity to represent experience as both psychological and sensual while injecting this portrayal with humour and individuality. Along with bringing new meaning and attention to metaphysical poetry, Eliot's article "The Metaphysical Poets" offered his now well-known notion of "unified sensibility," which some believe to imply the same thing as the word "metaphysical." His 1922 poem The Waste Land is also more understandable in light of his work as a critic. He had claimed that a poet should write "programmatic critique," that is, to advance their goals rather than to further "historical research." The Waste Land, as viewed through Eliot's critical lens, most likely reflects his sadness over World War I rather than an objective historical comprehension of it. Late in his career, Eliot devoted most of his creative energy to writing for the stage; some of his earlier analytical writing, in articles such as "Poetry and Theatre," "Hamlet and His Problems," and "The Possibility of a Poetic Drama," centred on the aesthetics of composing verse drama. Critical ReceptionRonald Bush, a writer, observes that Eliot's early poems, such as "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," "Portrait of a Lady," "La Figlia Che Piange," "Preludes," and "Rhapsody on a Windy Night" was both unique and compelling, and their assurance stunned contemporaries who were privileged to read them in the manuscript. Aiken, for example, remarked on "how crisp and complete and unique the whole thing was from the start"."The totality is present from the start." The reaction to Eliot's The Waste Land was varied at first. Bush points out that the piece was initially viewed accurately as a work of jazz-like syncopation-and, like 1920s jazz, genuinely iconoclastic. "Some reviewers, such as Edmund Wilson, Conrad Aiken, and Gilbert Seldes, believed it was the finest poetry ever written in English, while others thought it was arcane and purposefully difficult." One of the reviewers who appreciated Eliot was Edmund Wilson, who termed him "one of our only true poets." Wilson also highlighted some of Eliot's flaws as a poet. Wilson concedes The Waste Land has weaknesses ("its lack of structural consistency") but concludes, "I wonder whether there is a single another poem of similar length by a contemporary American that exhibits as great and diverse command of English poetry." Charles Powell was critical of Eliot, calling his poetry unintelligible. A problematic poem like The Waste Land also perplexed Time magazine editors. John Crowe Ransom has both favourable and bad things to say about Eliot's work. For example, while Ransom criticised The Waste Land for its "extreme detachment," he did not entirely dismiss Eliot's writing and acknowledged that Eliot was a skilled poet. In response to some of the typical complaints levelled about The Waste Land at the time, Gilbert Seldes commented, "A deeper look at the poem does more than elucidate the difficulties; it unveils the hidden shape of the work, [and] indicates how each item comes into place." Following the publication of The Four Quartets, Eliot's fame as a poet, as well as his influence in the academic, soared. Cynthia Ozick, in an article on Eliot published in 1989, refers to this period of impact as "the Age of Eliot," when Eliot "seemed pure zenith, a colossus, nothing less than a permanent luminary, fixed in the firmament like the sun and the moon." However, others, including Ronald Bush, remarked that the post-war period also marked the beginning of Eliot's literary decline: Eliot's conservative religious and political convictions began to seem less congenial in the postwar world, and other readers reacted with suspicion to his assertions of authority, obvious in Four Quartets and implicit in the earlier poetry. The result, fuelled by the intermittent rediscovery of Eliot's occasional anti-Semitic rhetoric, has been a progressive downward revision of his once towering reputation. Bush also mentions how Eliot's reputation "slid" dramatically following his death. He states, "It is sometimes thought to be too scholarly. Eliot was also chastised for his deadening neoclassicism. However, the numerous tributes from working poets of all schools published at his centennial in 1988 were significant evidence of his literary voice's formidable ongoing existence." Literary experts like Harold Bloom and Stephen Greenblatt see Eliot's poetry as fundamental to the English literary canon. "There is no doubt on significance as one of the great renovators of the English poetry dialect, whose effect on a whole generation of poets, critics, and intellectuals, in general, was huge," the editors of The Norton Anthology of English Literature wrote. His knowledge is restricted, and his interest in the vast middle ground of human experience (as opposed to the extremes of saint and sinner) is lacking." Despite this critique, these academics recognise "poetic ingenuity, exquisite craftsmanship, original accent, historical and representational value as a poet of the modern symbolist-Metaphysical tradition." AntisemitismThe portrayal of Jews in several of Eliot's poems has led to some critics accusing him of antisemitism, most vehemently in Anthony Julius' book T. S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism, and Literary Form (1996). "And the Jew perches on the window sill, the owner / Spawned in some estaminet of Antwerp," Eliot writes in "Gerontion," in the voice of the poem's old narrator. Another instance may be found in Eliot's poetry "Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar," in which he writes, "The rats are beneath the heaps. The Jew is beneath the lot. Money in furs." Julius says: "The anti-Semitism is palpable. It acts as a clear signal to the reader." Harold Bloom, Christopher Ricks, George Steiner, Tom Paulin, and James Fenton all agreed with Julius. "What is still more important [than cultural homogeneity] is the unity of religious background, and reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable," Eliot wrote of societal tradition and coherence in lectures delivered at the University of Virginia in 1933 (published in 1934 under the title After Strange Gods A Primer of Modern Heresy). Eliot separates himself from the Fascist movements of the 1930s in his 1934 pageant drama The Rock by caricaturing Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts, who "firmly refuse to descend to palaver with anthropoid Jews." Totalitarianism's "new evangels" are depicted as antithetical to the spirit of Christianity. Craig Raine attempted to defend Eliot against the allegation of anti-Semitism in his books In Defence of T. S. Eliot (2001) and T. S. Eliot (2006). Raine's reasoning did not persuade Paul Dean.

Next TopicCassidy Hutchinson

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share