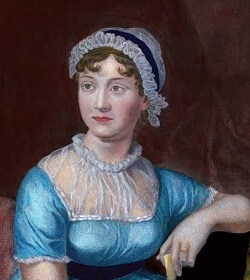

Jane Austen

She achieved modest success but little fame during her lifetime with the publication of Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1816). She wrote two other novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, both of which were published posthumously in 1818, and started another, Sanditon, but died before it was finished. She also left three volumes of manuscript juvenile writings, the short epistolary novel Lady Susan, and the unfinished novel The Watsons. Austen's reputation grew significantly after her death, and her six full-length novels are rarely out of print. Her posthumous reputation changed dramatically in 1833, when her novels were republished in Richard Bentley's Standard Novels series, illustrated by Ferdinand Pickering, and sold as a set. They gradually gained wider recognition and a large readership. In 1869, fifty-two years after her death, her nephew's publication of A Memoir of Jane Austen introduced an eager audience to a compelling version of her writing career and supposedly uneventful life. Austen has sparked numerous critical essays and literary anthologies. Her novels have inspired numerous films, ranging from the 1940s Pride and Prejudice to more recent works such as Sense and Sensibility (1995) and Love & Friendship (1999). Her BiographyExcept for a few letters and biographical notes written by Austen's family members, there is little biographical information about her life. Austen may have written up to 3,000 letters during her lifetime, but only 161 have survived. Cassandra, her older sister, burned or destroyed the majority of letters she received in 1843 to prevent them from falling into the hands of relatives and to ensure that "younger nieces did not read any of Jane Austen's sometimes acid or forthright comments on neighbours or family members." Cassandra intended to shield the family's reputation from her sister's candour, so she withheld information about family illnesses and misfortunes. Henry Thomas Austen's 1818 "Biographical Notice" was the first Austen biography. It was published in a posthumous edition of Northanger Abbey and included excerpts from two letters, which other family members rejected. Details about Austen's life were omitted or embellished in her nephew's A Memoir of Jane Austen, published in 1869, and in William and Richard Arthur Austen-biography Leigh's Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters, published in 1913, all of which included new letters. The legend created by the family and relatives reflected their bias toward portraying the image of "good quiet Aunt Jane," a woman whose domestic situation was happy and whose family was the mainstay of her life. Modern biographers include details previously excised from letters and family biographies, but Austen scholar Jan Fergus explains that the challenge is to avoid presenting the opposite view - that Austen was "an embittered, disappointed woman trapped in a thoroughly unpleasant family." Family

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775, in Steventon, Hampshire. Her arrival was a month later than her parents had anticipated; her father wrote in a letter that her mother "certainly expected to have been brought to bed a month ago." He went on to say that the newborn baby was "a present toy for Cassy and a future companion." The winter of 1776 was particularly harsh, and she was not baptised with the single name Jane until 5 April at the local church. George Austen (1731-1805) was rector of the Anglican parishes of Steventon and Deane. He came from an extended and prosperous family of wool merchants. The wealth was divided as each generation of eldest sons received inheritances, and George's branch of the family fell into poverty. As children, he and his two sisters were orphaned and had to be cared for by relatives. Philadelphia Austen, George Austen's fifteen-year-old sister, was apprenticed to a milliner in Covent Garden in 1745. George entered St John's College, Oxford, at the age of sixteen, where he most likely met Cassandra Leigh (1739-1827). Her father was the rector of All Souls College, Oxford, where she grew up among the gentry, and she came from a prominent Leigh family. James, her eldest brother, inherited a fortune and a large estate from his great-aunt Perrot on the condition that he change his name to Leigh-Perrot. When George Austen and Cassandra Leigh exchanged miniatures, they were probably engaged. He had received the living of Steventon parish from his second cousin Thomas Knight's wealthy husband. They married by licence on April 26, 1764, at St Swithin's Church in Bath, in a simple ceremony, two months after Cassandra's father died. With George's small annual salary, their income was modest; Cassandra brought to the marriage the expectation of a small inheritance at the time of her mother's death. The Austens moved into the nearby Deane rectory while Steventon, a 16th-century house in disrepair, underwent necessary renovations. Cassandra had three children during her time at Deane: James in 1765, George in 1766, and Edward in 1767. Her custom was to keep an infant at home for several months before placing it with Elizabeth Littlewood, a nearby woman, to nurse and raise for twelve to eighteen months. EducationMrs. Ann Cawley sent Austen and her sister Cassandra to Oxford to be educated in 1783, and she later took them to Southampton when she moved there later that year. Both girls were sent home in the autumn after contracting typhus, and Austen nearly died. Austen was homeschooled until she began attending boarding school in Reading with her sister in early 1785 at the Reading Abbey Girls' School, which was run by Mrs. La Tournelle had a cork leg and a passion for theatre. The school curriculum most likely included French, spelling, needlework, dancing and music, and possibly drama. The sisters returned home before December 1786 because the Austen family couldn't afford the two girls' school fees. Austen "never again lived anywhere outside the bounds of her immediate family environment" after 1786. Her father and brothers James and Henry guided her through the rest of her education through reading. Austen, according to Irene Collins, "used some of the same school books as the boys" her father tutored. Austen appeared to have unrestricted access to both her father's library and the library of a family friend, Warren Hastings. These collections combined to form a large and diverse library. Her father was also tolerant of Austen's sometimes risqué writing experiments and provided both sisters with expensive paper and other writing materials. The private theatre was an essential part of Austen's education. The family and friends staged a series of plays in the rectory barn from her childhood, including Richard Sheridan's The Rivals (1775) and David Garrick's Bon Ton. The prologues and epilogues were written by Austen's eldest brother James, and she most likely participated in these activities, first as a spectator and then as a participant. The majority of the plays were comedies, indicating how Austen's satirical talents were developed. She began writing plays when she was 12 years old, and she wrote three short plays during her adolescence. The Juvenilia

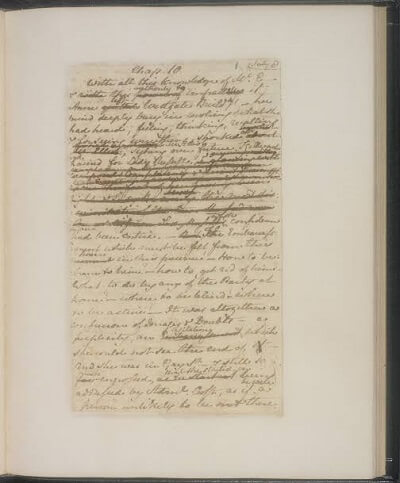

Austen began writing poems and stories for herself and her family as early as the age of eleven, and possibly earlier. According to Janet Todd, these works "are full of anarchic fantasies of female power, license, illicit behavior, and general high spirits," with details of daily life exaggerated and standard plot devices parodied. Austen compiled fair copies of twenty-nine early works into three bound notebooks, now known as the Juvenilia, between 1787 and 1793. The three notebooks are titled "Volume the First," "Volume the Second," and "Volume the Third," and they contain 90,000 words she wrote during those years. According to scholar Richard Jenkyns, the Juvenilia are frequently "boisterous" and "anarchic," He compares them to the work of 18th-century novelist Laurence Sterne. Among these works is Love and Friendship, a satirical novel in letters written at the age of fourteen in 1790 in which she mocked popular novels of sensibility. The following year, she completed The History of England, a thirty-four-page manuscript accompanied by thirteen watercolour miniatures by her sister, Cassandra. Austen's History was a parody of popular historical writing, specifically Oliver Goldsmith's History of England (1764). Honan speculates that Austen decided to "write for profit, to make stories her central effort," that is, to become a professional writer, not long after finishing Love and Friendship. Austen began writing longer, more sophisticated works around the age of eighteen. Austen began writing Catharine or the Bower in August 1792, when she was seventeen, foreshadowing her mature work, particularly Northanger Abbey; it was left unfinished, and the story was picked up in Lady Susan, which Todd describes as less foreshadowing than Catharine. A year later, she began but abandoned Sir Charles Grandison or the Happy Man, a comedy in six acts, which she later returned to and finished around 1800. This was a short parody of various school textbook abridgements of Austen's favourite contemporary novel, Samuel Richardson's The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753). Early Manuscripts

Following the completion of Lady Susan, Austen began work on her first full-length novel, Elinor and Marianne. It was read to the family "before 1796," according to her sister, and was told through a series of letters. There is no way to know how much of the original draught survived in the novel published anonymously in 1811 as Sense and Sensibility without surviving original manuscripts. In 1796, Austen began work on her second novel, First Impressions (later renamed Pride and Prejudice). She finished the first draught in August 1797, at the age of 21; as with all of her novels, Austen read it aloud to her family as she worked on it, and it became a "established favourite." Her father made the first attempt to publish one of her novels at this time. In November 1797, George Austen wrote to Thomas Cadell, a well-known London publisher, asking if he would consider publishing First Impressions. Cadell marked Mr. Austen's letter "Declined by Return of Post." Austen might not have been aware of her father's efforts. Following the completion of First Impressions, Austen returned to Elinor and Marianne and heavily revised it from November 1797 to mid-1798; she abandoned the epistolary format in favour of third-person narration and produced something resembling Sense and Sensibility. In 1797, Austen met Eliza de Feuillide, a French aristocrat whose first husband, the Comte de Feuillide, had been guillotined, forcing her to flee to Britain, where she married Henry Austen. The description of the Comte de Feuillide's execution given by his widow instilled in Austen an intense fear of the French Revolution that lasted the rest of her life. After finishing revisions on Elinor and Marianne, Austen began writing the third novel with the working title Susan-later Northanger Abbey-a satire on the popular Gothic fiction in the middle of 1798. Austen finished her work a year later. In early 1803, Henry Austen offered Susan to a London publisher, Benjamin Crosby, who paid £10 for the copyright. Crosby promised early publication and even went so far as to advertise the book as "in the press publicly," but did nothing else. The manuscript remained unpublished in Crosby's hands until Austen repurchased the copyright from him in 1816. PublishAusten, like many other female authors of the time, published her works anonymously. The ideal roles for a woman at the time were wife and mother, and writing for women was regarded as a secondary form of activity; a woman who wished to be a full-time writer was thought to be degrading her femininity, so books by women were usually published anonymously to maintain the conceit that the female writer was only posting as a sort of part-time job, and was not seeking to become a "literary lioness" (i.e. a celebrity). Austen published four novels during her time at Chawton, all of which were well-received. The publisher Thomas Egerton agreed to publish Sense and Sensibility through her brother Henry, and it, like all of Austen's novels except Pride and Prejudice, was published "on commission," that is, at the author's financial risk. When publishing on commission, publishers would advance the costs of publication, repay themselves as books were sold, and then charge a 10% commission on each book sold, with the author receiving the remainder. If a novel's costs were not recouped through sales, the author was held accountable. The alternative to selling through commission was to sell the copyright, in which an author received a one-time payment from the publisher for the manuscript, as was the case with Pride and Prejudice. Austen was wary of this method of publishing after her experience with Susan (the manuscript that became Northanger Abbey), in which she sold the copyright to the publisher Crosby & Sons, who did not publish the book, forcing her to buy back the copyright to have her work published. The final option, selling by subscription, in which a group of people agreed to buy a book in advance, was not available to Austen because only well-known authors or those with an influential aristocratic patron who would recommend an upcoming book to their friends could sell by subscription. Sense and Sensibility was published in October 1811 and was written "By a Lady." Austen discovered that the Prince Regent admired her novels and had a copy in each of his residences. In November 1815, the Prince Regent's librarian, James Stanier Clarke, invited Austen to the Prince's London residence and suggested that Austen dedicate the upcoming Emma to the Prince. Even though Austen disliked the Prince Regent, she couldn't say no to the request. Austen disliked the Prince Regent because of his womanising, gambling, drinking, spendthrift ways, and generally shady behavior. According to Hints from Various Quarters, she later wrote Plan of a Novel, a satirical outline of the "perfect novel" based on the librarian's numerous suggestions for a future Austen novel. Genre and Style of WritingAusten's works are part of the transition from sentimental novels of the second half of the 18th century to 19th-century literary realism. The earliest English novelists, Richardson, Henry Fielding, and Tobias Smollett, were followed by the school of sentimentalists and romantics such as Walter Scott, Horace Walpole, Clara Reeve, Ann Radcliffe, and Oliver Goldsmith, whose style and genre Austen rejected, returning the novel on a "slender thread" to Richardson and Fielding's tradition of a "realistic study of manners." Literary critics F. R. Leavis and Ian Watt placed her in the tradition of Richardson and Fielding in the mid-twentieth century; both believe she used their tradition of "irony, realism, and satire to form an author superior to both." She avoided popular Gothic fiction, which typically featured a heroine stranded in a remote location, such as a castle or abbey (32 novels between 1784 and 1818 contain the word "abbey" in their title). However, she alludes to the trope in Northanger Abbey, with the heroine, Catherine, anticipating a move to a remote location. Rather than outright rejecting or parodying the genre, Austen transforms it by juxtaposing reality, with descriptions of elegant rooms and modern conveniences, with the heroine's "novel-fueled" desires. She also does not completely dismiss Gothic fiction; instead, she transforms settings and situations so that the heroine is still imprisoned, but her confinement is mundane and real-regulated manners and the strict rules of the ballroom. According to critic Keymer, despite being a parody of popular sentimental fiction, "Marianne in her sentimental histrionics responds to the calculating world... with a quite justifiable scream of female distress" in Sense and Sensibility. Austen's plots emphasise women's traditional reliance on marriage for social and economic security. The 18th-century novel lacked the seriousness of its 19th-century counterparts, when novels were regarded as "the natural vehicle for discussion and ventilation of what mattered in life." According to critic John Bayley, rather than delving too deeply into her characters' psyches, Austen enjoys and imbues them with humor. He believes that her wit and irony stem from her own belief that comedy "is the saving grace of life." Austen's fame stems in part from her historical and literary significance as the first woman to write great comic novels. Samuel Johnson's influence can be seen in her decision to write "a representation of life as may excite mirth." Her humor stems from her modesty and lack of superiority, which allows her most successful characters, such as Elizabeth Bennet, to transcend the trivialities of life that the more foolish characters are too preoccupied with. Austen used comedy to explore the individualism of women's lives and gender relations, and it appears that she used it to find the goodness in life, frequently fusing it with "ethical sensibility," creating artistic tension. Death

By early 1816, Austen was feeling ill, but she ignored the symptoms. Her decline was obvious by the middle of the year, and she began a slow, irregular deterioration. The large percentage of biographers rely on Zachary Cope's 1964 retrospective diagnosis and list Addison's disease as her cause of death, though her final illness has also been described as being caused by Hodgkin's lymphoma. "I am ashamed to say that the shock of my Uncle's Will brought on a relapse... but a weak Body must excuse weak Nerves," she wrote after her uncle died and left his entire fortune to his wife, effectively disinheriting his relatives. Despite her illness, Austen continued to work. She rewrote the final two chapters of The Elliots after being dissatisfied with the ending, which she completed on August 6, 1816. In January 1817, Austen began The Brothers (titled Sanditon when published in 1925), completing twelve chapters before stopping work in mid-March 1817, probably due to illness. Diana Parker, Sanditon's heroine, is described by Todd as a "energetic invalid." Austen mocked hypochondriacs in the novel, and despite describing the heroine as "bilious," five days after abandoning the novel, she wrote about herself that she was turning "every wrong colour" and living "chiefly on the sofa." On March 18, 1817, she put down her pen and made a note of it. Austen made light of her illness, referring to it as "bile" and rheumatism. As her illness progressed, she had difficulty walking and was exhausted; by mid-April, she was bedridden. Cassandra and Henry brought her to Winchester for treatment in May, by which time she was in excruciating pain and ready to die. Austen died on July 18, 1817, at the age of 41, in Winchester. Henry arranged for his sister to be buried in the north aisle of the nave of Winchester Cathedral, thanks to his clerical connections. Her brother James' epitaph praises Austen's personal qualities, expresses hope for her salvation, and mentions the "extraordinary endowments of her mind," but does not explicitly mention her literary achievements.

Next TopicBruno Mars

|

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

For Videos Join Our Youtube Channel: Join Now

Feedback

- Send your Feedback to [email protected]

Help Others, Please Share